* **`.dmg`**: Apple Disk Image files are very frequent for installers.

* **`.kext`**: It must follow a specific structure and it's the OS X version of a driver.

* **`.plist`**: Also known as property list stores information in XML or binary format.

* Can be XML or binary. Binary ones can be read with:

*`defaults read config.plist`

*`/usr/libexec/PlistBuddy -c print config.plsit`

*`plutil -p config.plist`

* **`.app`**: Apple applications that follows directory structure.

* **`.dylib`**: Dynamic libraries \(like Windows DLL files\)

* **`.pkg`**: Are the same as xar \(eXtensible Archive format\). The installer command can be use to install the contents of these files.

### File hierarchy layout

* **/Applications**: The installed apps should be here. All the users will be able to access them.

* **/bin**: Command line binaries

* **/cores**: If exists, it's used to store core dumps

* **/dev**: Everything is treated as a file so you may see hardware devices stored here.

* **/etc**: Configuration files

* **/Library**: A lot of subdirectories and files related to preferences, caches and logs can be found here. A Library folder exists in root and on each user's directory.

* **/private**: Undocumented but a lot of the mentioned folders are symbolic links to the private directory.

* **/sbin**: Essential system binaries \(related to administration\)

* **/System**: File fo making OS X run. You should find mostly only Apple specific files here \(not third party\).

* **/tmp**: Files are deleted after 3 days \(it's a soft link to /private/tmp\)

* **/Users**: Home directory for users.

* **/usr**: Config and system binaries

* **/var**: Log files

* **/Volumes**: The mounted drives will apear here.

* **/.vol**: Running `stat a.txt` you obtain something like `16777223 7545753 -rw-r--r-- 1 username wheel ...` where the first number is the id number of the volume where the file exists and the second one is the inode number. You can access the content of this file through /.vol/ with that information running `cat /.vol/16777223/7545753`

### Special MacOS files and folders

* **`.DS_Store`**: This file is on each directory, it saves the attributes and customisations of the directory.

* **`.Spotlight-V100`**: This folder appears on the root directory of every volume on the system.

* **`.metadata_never_index`**: If this file is at the root of a volume Spotlight won't index that volume.

* **`<name>.noindex`**: Files and folder with this extension won't be indexed by Spotlight.

* **`$HOME/Library/Preferences/com.apple.LaunchServices.QuarantineEventsV`**2: Contains information about downloaded files, like the URL from where they were downloaded.

* **`/var/log/system.log`**: Main log of OSX systems. com.apple.syslogd.plist is responsible for the execution of syslogging \(you can check if it's disabled looking for "com.apple.syslogd" in `launchctl list`.

* **`/private/var/log/asl/*.asl`**: These are the Apple System Logs which may contain interesting information.

* **`$HOME/Library/Preferences/com.apple.recentitems.plist`**: Stores recently accessed files and applications through "Finder".

* **`$HOME/Library/Preferences/com.apple.loginitems.plsit`**: Stores items to launch upon system startup

* **`$HOME/Library/Logs/DiskUtility.log`**: Log file for thee DiskUtility App \(info about drives, including USBs\)

* **`/Library/Preferences/SystemConfiguration/com.apple.airport.preferences.plist`**: Data about wireless access points.

* **`/private/var/db/launchd.db/com.apple.launchd/overrides.plist`**: List of daemons deactivated.

* **`/private/etc/kcpassword`**: If autologin is enabled this file will contain the users login password XORed with a key.

### Common users

* **Daemon**: User reserved for system daemons

* **Guest**: Account for guests with very strict permissions

* **Nobody**: Processes are executed with this user when minimal permissions are required

* **Root**

### User Privileges

* **Standard User:** The most basic of users. This user needs permissions granted from an admin user when attempting to install software or perform other advanced tasks. They are not able to do it on their own.

* **Admin User**: A user who operates most of the time as a standard user but is also allowed to perform root actions such as install software and other administrative tasks. All users belonging to the admin group are **given access to root via the sudoers file**.

* **Root**: Root is a user allowed to perform almost any action \(there are limitations imposed by protections like System Integrity Protection\).

* For example root won't be able to place a file inside `/System`

### **File ACLs**

When the file contains ACLs you will **find a "+" when listing the permissions like in**:

```bash

ls -ld Movies

drwx------+ 7 username staff 224 15 Apr 19:42 Movies

```

You can **read the ACLs** of the file with:

```bash

ls -lde Movies

drwx------+ 7 username staff 224 15 Apr 19:42 Movies

0: group:everyone deny delete

```

You can find **all the files with ACLs** with \(this is veeery slow\):

```bash

ls -RAle / 2>/dev/null | grep -E -B1 "\d: "

```

### Resource Forks or MacOS ADS

This is a way to obtain **Alternate Data Streams in MacOS** machines. You can save content inside an extended attribute called **com.apple.ResourceFork** inside a file by saving it in **file/..namedfork/rsrc**.

```bash

echo "Hello" > a.txt

echo "Hello Mac ADS" > a.txt/..namedfork/rsrc

xattr -l a.txt #Read extended attributes

com.apple.ResourceFork: Hello Mac ADS

ls -l a.txt #The file length is still q

-rw-r--r--@ 1 username wheel 6 17 Jul 01:15 a.txt

```

You can **find all the files containing this extended attribute** with:

The files `/System/Library/CoreServices/CoreTypes.bundle/Contents/Resources/System` contains the risk associated to files depending on the file extension.

The possible categories include the following:

* **LSRiskCategorySafe**: **Totally****safe**; Safari will auto-open after download

* **LSRiskCategoryNeutral**: No warning, but **not auto-opened**

* **LSRiskCategoryUnsafeExecutable**: **Triggers** a **warning** “This file is an application...”

* **LSRiskCategoryMayContainUnsafeExecutable**: This is for things like archives that contain an executable. It **triggers a warning unless Safari can determine all the contents are safe or neutral**.

### Remote Access Services

You can enable/disable these services in "System Preferences" --> Sharing

* **VNC**, known as “Screen Sharing”

* **SSH**, called “Remote Login”

* **Apple Remote Desktop** \(ARD\), or “Remote Management”

_**Gatekeeper**_ is designed to ensure that, by default, **only trusted software runs on a user’s Mac**. Gatekeeper is used when a user **downloads** and **opens** an app, a plug-in or an installer package from outside the App Store. Gatekeeper verifies that the software is **signed by** an **identified developer**, is **notarised** by Apple to be **free of known malicious content**, and **hasn’t been altered**. Gatekeeper also **requests user approval** before opening downloaded software for the first time to make sure the user hasn’t been tricked into running executable code they believed to simply be a data file.

In order for an **app to be notarised by Apple**, the developer needs to send the app for review. Notarization is **not App Review**. The Apple notary service is an **automated system** that **scans your software for malicious content**, checks for code-signing issues, and returns the results to you quickly. If there are no issues, the notary service generates a ticket for you to staple to your software; the notary service also **publishes that ticket online where Gatekeeper can find it**.

When the user first installs or runs your software, the presence of a ticket \(either online or attached to the executable\) **tells Gatekeeper that Apple notarized the software**. **Gatekeeper then places descriptive information in the initial launch dialog** indicating that Apple has already checked for malicious content.

Upon download of an application, a particular **extended file attribute** \("quarantine flag"\) can be **added** to the **downloaded****file**. This attribute **is added by the application that downloads the file**, such as a **web****browser** or email client, but is not usually added by others like common BitTorrent client software.

When a user executes a "quarentined" file, **Gatekeeper** is the one that **performs the mentioned actions** to allow the execution of the file.

Should malware make its way onto a Mac, macOS also includes technology to remediate infections. The _Malware Removal Tool \(MRT\)_ is an engine in macOS that remediates infections based on updates automatically delivered from Apple \(as part of automatic updates of system data files and security updates\). **MRT removes malware upon receiving updated information** and it continues to check for infections on restart and login. MRT doesn’t automatically reboot the Mac. \(From [here](https://support.apple.com/en-gb/guide/security/sec469d47bd8/web#:~:text=The%20Malware%20Removal%20Tool%20%28MRT,data%20files%20and%20security%20updates%29.)\)

Apple issues the **updates for XProtect and MRT automatically** based on the latest threat intelligence available. By default, macOS checks for these updates **daily**. Notarisation updates are distributed using CloudKit sync and are much more frequent.

### TCC

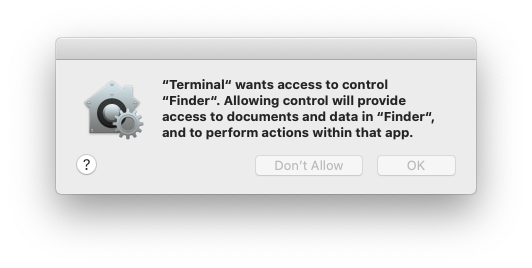

**TCC \(Transparency, Consent, and Control\)** is a mechanism in macOS to **limit and control application access to certain features**, usually from a privacy perspective. This can include things such as location services, contacts, photos, microphone, camera, accessibility, full disk access, and a bunch more.

From a user’s perspective, they see TCC in action **when an application wants access to one of the features protected by TCC**. When this happens the user is prompted with a dialog asking them whether they want to allow access or not. This response is then stored in the TCC database.

The TCC database is just a **sqlite3 database**, which makes the task of investigating it much simpler. There are two different databases, a global one in `/Library/Application Support/com.apple.TCC/TCC.db` and a per-user one located in `/Users/<username>/Library/Application Support/com.apple.TCC/TCC.db`. The first database is **protected from editing with SIP**\(System Integrity Protection\), but you can read them by granting terminal\(or your editor\) full disk access.

This information was [taken from here](https://rainforest.engineering/2021-02-09-macos-tcc/) \(read the **original source for more information**\).

Some protected directories:

* $HOME/Desktop

* $HOME/Documents

* $HOME/Downloads

* iCloud Drive

* ...

Unprotected directories:

* $HOME \(itself\)

* $HOME/.ssh, $HOME/.aws, etc

* /tmp

Here you can find examples of how **malware has been able to bypass this protection**:

MacOS Sandbox works with the kernel extension Seatbelt. It makes applications run inside the sandbox **need to request access to resources outside of the limited sandbox**. This helps to ensure that **the application will be accessing only expected resources** and if it wants to access anything else it will need to ask for permissions to the user.

Important **system services** also run inside their own custom **sandbox** such as the mdnsresponder service. You can view these custom **sandbox profiles** inside the **`/usr/share/sandbox`** directory. Other sandbox profiles can be checked in [https://github.com/s7ephen/OSX-Sandbox--Seatbelt--Profiles](https://github.com/s7ephen/OSX-Sandbox--Seatbelt--Profiles).

* [https://desi-jarvis.medium.com/office365-macos-sandbox-escape-fcce4fa4123c](https://desi-jarvis.medium.com/office365-macos-sandbox-escape-fcce4fa4123c) \(they are able to write files outside the sandbox whose name starts with `~$`\).

This protection was enabled to **help keep root level malware from taking over certain parts** of the operating system. Although this means **applying limitations to the root user** many find it to be worthwhile trade off.

The most notable of these limitations are that **users can no longer create, modify, or delete files inside** of the following four directories in general:

* /System

* /bin

* /sbin

* /usr

Note that there are **exceptions specified by Apple**: The file **`/System/Library/Sandbox/rootless.conf`** holds a list of **files and directories that cannot be modified**. But if the line starts with an **asterisk** it means that it can be **modified** as **exception**.

For example, the config lines:

```bash

/usr

* /usr/libexec/cups

* /usr/local

* /usr/share/man

```

Means that `/usr`**cannot be modified****except** for the **3 allowed** folders allowed.

The final exception to these rules is that **any installer package signed with the Apple’s certificate can bypass SIP protection**, but **only Apple’s certificate**. Packages signed by standard developers will still be rejected when trying to modify SIP protected directories.

Note that if **a file is specified** in the previous config file **but** it **doesn't exist, it can be created**. This might be used by malware to obtain stealth persistence. For example, imagine that a **.plist** in `/System/Library/LaunchDaemons` appears listed but it doesn't exist. A malware may c**reate one and use it as persistence mechanism.**

**SIP** handles a number of **other limitations as well**. Like it **doesn't allows for the loading of unsigned kexts**. SIP is also responsible for **ensuring** that no OS X **system processes are debugged**. This also means that Apple put a stop to dtrace inspecting system processes.

For more **information about SIP** read the following response: [https://apple.stackexchange.com/questions/193368/what-is-the-rootless-feature-in-el-capitan-really](https://apple.stackexchange.com/questions/193368/what-is-the-rootless-feature-in-el-capitan-really)

When checking some **malware sample** you should always **check the signature** of the binary as the **developer** that signed it may be already **related** with **malware.**

An **ASEP** is a location on the system that could lead to the **execution** of a binary **without****user****interaction**. The main ones used in OS X take the form of plists.

**`launchd`** is the **first****process** executed by OX S kernel at startup and the last one to finish at shut down. It should always have the **PID 1**. This process will **read and execute** the configurations indicated in the **ASEP****plists** in:

*`/Library/LaunchAgents`: Per-user agents installed by the admin

*`/Library/LaunchDaemons`: System-wide daemons installed by the admin

*`/System/Library/LaunchAgents`: Per-user agents provided by Apple.

*`/System/Library/LaunchDaemons`: System-wide daemons provided by Apple.

When a user logs in the plists located in `/Users/$USER/Library/LaunchAgents` and `/Users/$USER/Library/LaunchDemons` are started with the **logged users permissions**.

The **main difference between agents and daemons is that agents are loaded when the user logs in and the daemons are loaded at system startup** \(as there are services like ssh that needs to be executed before any user access the system\). Also agents may use GUI while daemons need to run in the background.

<key>RunAtLoad</key><true/><!--Execute at system startup-->

<key>StartInterval</key>

<integer>800</integer><!--Execute each 800s-->

<key>KeepAlive</key>

<dict>

<key>SuccessfulExit</key></false><!--Re-execute if exit unsuccessful-->

<!--If previous is true, then re-execute in successful exit-->

</dict>

</dict>

</plist>

```

There are cases where an **agent needs to be executed before the user logins**, these are called **PreLoginAgents**. For example, this is useful to provide assistive technology at login. They can be found also in `/Library/LaunchAgents`\(see [**here**](https://github.com/HelmutJ/CocoaSampleCode/tree/master/PreLoginAgents) an example\).

{% hint style="info" %}

New Daemons or Agents config files will be **loaded after next reboot or using**`launchctl load <target.plist>` It's **also possible to load .plist files without that extension** with `launchctl -F <file>` \(however those plist files won't be automatically loaded after reboot\).

It's also possible to **unload** with `launchctl unload <target.plist>` \(the process pointed by it will be terminated\),

To **ensure** that there isn't **anything** \(like an override\) **preventing** an **Agent** or **Daemon****from****running** run: `sudo launchctl load -w /System/Library/LaunchDaemos/com.apple.smdb.plist`

In MacOS several folders executing scripts with **certain frequency** can be found in:

```bash

ls -lR /usr/lib/cron/tabs/ /private/var/at/jobs /etc/periodic/

```

There you can find the regular **cron****jobs**, the **at****jobs** \(not very used\) and the **periodic****jobs** \(mainly used for cleaning temporary files\). The daily periodic jobs can be executed for example with: `periodic daily`.

“At tasks” are used to **schedule tasks at specific times**.

These tasks differ from cron in that **they are one time tasks** t**hat get removed after executing**. However, they will **survive a system restart** so they can’t be ruled out as a potential threat.

By **default** they are **disabled** but the **root** user can **enable****them** with:

The root user one is stored in `/private/var/root/Library/Preferences/com.apple.loginwindow.plist`

### Startup Items

This is deprecated, so nothing should be found in the following directories.

A **StartupItem** is a **directory** that gets **placed** in one of these two folders. `/Library/StartupItems/` or `/System/Library/StartupItems/`

After placing a new directory in one of these two locations, **two more items** need to be placed inside that directory. These two items are a **rc script****and a plist** that holds a few settings. This plist must be called “**StartupParameters.plist**”.

{% code title="StartupParameters.plist" %}

```markup

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<!DOCTYPE plist PUBLIC "-//Apple Computer//DTD PLIST 1.0//EN" "http://www.apple.com/DTDs/PropertyList-1.0.dtd">

<plistversion="1.0">

<dict>

<key>Description</key>

<string>This is a description of this service</string>

<key>OrderPreference</key>

<string>None</string><!--Other req services to execute before this -->

<key>Provides</key>

<array>

<string>superservicename</string><!--Name of the services provided by this file -->

</array>

</dict>

</plist>

```

{% endcode %}

{% code title="superservicename" %}

```bash

#!/bin/sh

. /etc/rc.common

StartService(){

touch /tmp/superservicestarted

}

StopService(){

rm /tmp/superservicestarted

}

RestartService(){

echo "Restarting"

}

RunService "$1"

```

{% endcode %}

### /etc/rc.common

It's also possible to place here **commands that will be executed at startup.** Example os regular rc.common script:

* **`/private/var/vm/swapfile0`**: This file is used as a **cache when physical memory fills up**. Data in physical memory will be pushed to the swapfile and then swapped back into physical memory if it’s needed again. More than one file can exist in here. For example, you might see swapfile0, swapfile1, and so on.

* **`/private/var/vm/sleepimage`**: When OS X goes into **hibernation**, **data stored in memory is put into the sleepimage file**. When the user comes back and wakes the computer, memory is restored from the sleepimage and the user can pick up where they left off.

By default in modern MacOS systems this file will be encrypted, so it might be not recuperable.

* However, the encryption of this file might be disabled. Check the out of `sysctl vm.swapusage`.

### Dumping memory with osxpmem

In order to dump the memory in a MacOS machine you can use [**osxpmem**](https://github.com/google/rekall/releases/download/v1.5.1/osxpmem-2.1.post4.zip).

```bash

#Dump raw format

sudo osxpmem.app/osxpmem --format raw -o /tmp/dump_mem

#Dump aff4 format

sudo osxpmem.app/osxpmem -o /tmp/dump_mem.aff4

```

If you find this error: `osxpmem.app/MacPmem.kext failed to load - (libkern/kext) authentication failure (file ownership/permissions); check the system/kernel logs for errors or try kextutil(8)` You can fix it doing:

```bash

sudo cp -r osxpmem.app/MacPmem.kext "/tmp/"

sudo kextutil "/tmp/MacPmem.kext"

#Allow the kext in "Security & Privacy --> General"

sudo osxpmem.app/osxpmem --format raw -o /tmp/dump_mem

```

**Other errors** might be fixed by **allowing the load of the kext** in "Security & Privacy --> General", just **allow** it.

You can also use this **oneliner** to download the application, load the kext and dump the memory:

```bash

cd /tmp; wget https://github.com/google/rekall/releases/download/v1.5.1/osxpmem-2.1.post4.zip; unzip osxpmem-2.1.post4.zip; chown -R root:wheel osxpmem.app/MacPmem.kext; kextload osxpmem.app/MacPmem.kext; osxpmem.app/osxpmem --format raw -o /tmp/dump_mem

```

## Passwords

### Shadow Passwords

Shadow password is stored withe the users configuration in plists located in **`/var/db/dslocal/nodes/Default/users/`**.

The following oneliner can be use to dump **all the information about the users** \(including hash info\):

```bash

for l in /var/db/dslocal/nodes/Default/users/*; do if [ -r "$l" ];then echo "$l"; defaults read "$l"; fi; done

```

\*\*\*\*[**Scripts like this one**](https://gist.github.com/teddziuba/3ff08bdda120d1f7822f3baf52e606c2) or [**this one**](https://github.com/octomagon/davegrohl.git) can be used to transform the hash to **hashcat****format**.

The attacker still needs to gain access to the system as well as escalate to **root** privileges in order to run **keychaindump**. This approach comes with its own conditions. As mentioned earlier, **upon login your keychain is unlocked by default** and remains unlocked while you use your system. This is for convenience so that the user doesn’t need to enter their password every time an application wishes to access the keychain. If the user has changed this setting and chosen to lock the keychain after every use, keychaindump will no longer work; it relies on an unlocked keychain to function.

It’s important to understand how Keychaindump extracts passwords out of memory. The most important process in this transaction is the ”**securityd**“ **process**. Apple refers to this process as a **security context daemon for authorization and cryptographic operations**. The Apple developer libraries don’t say a whole lot about it; however, they do tell us that securityd handles access to the keychain. In his research, Juuso refers to the **key needed to decrypt the keychain as ”The Master Key“**. A number of steps need to be taken to acquire this key as it is derived from the user’s OS X login password. If you want to read the keychain file you must have this master key. The following steps can be done to acquire it. **Perform a scan of securityd’s heap \(keychaindump does this with the vmmap command\)**. Possible master keys are stored in an area flagged as MALLOC\_TINY. You can see the locations of these heaps yourself with the following command:

**Keychaindump** will then search the returned heaps for occurrences of 0x0000000000000018. If the following 8-byte value points to the current heap, we’ve found a potential master key. From here a bit of deobfuscation still needs to occur which can be seen in the source code, but as an analyst the most important part to note is that the necessary data to decrypt this information is stored in securityd’s process memory. Here’s an example of keychain dump output.

Base on this comment [https://github.com/juuso/keychaindump/issues/10\#issuecomment-751218760](https://github.com/juuso/keychaindump/issues/10#issuecomment-751218760) it looks like this tools isn't working anymore in Big Sur.

\*\*\*\*[**Chainbreaker**](https://github.com/n0fate/chainbreaker) can be used to extract the following types of information from an OSX keychain in a forensically sound manner:

* Hashed Keychain password, suitable for cracking with [hashcat](https://hashcat.net/hashcat/) or [John the Ripper](https://www.openwall.com/john/)

* Internet Passwords

* Generic Passwords

* Private Keys

* Public Keys

* X509 Certificates

* Secure Notes

* Appleshare Passwords

Given the keychain unlock password, a master key obtained using [volafox](https://github.com/n0fate/volafox) or [volatility](https://github.com/volatilityfoundation/volatility), or an unlock file such as SystemKey, Chainbreaker will also provide plaintext passwords.

Without one of these methods of unlocking the Keychain, Chainbreaker will display all other available information.

The **kcpassword** file is a file that holds the **user’s login password**, but only if the system owner has **enabled automatic login**. Therefore, the user will be automatically logged in without being asked for a password \(which isn't very secure\).

The password is stored in the file **`/etc/kcpassword`** xored with the key **`0x7D 0x89 0x52 0x23 0xD2 0xBC 0xDD 0xEA 0xA3 0xB9 0x1F`**. If the users password is longer than the key, the key will be reused.

This makes the password pretty easy to recover, for example using scripts like [**this one**](https://gist.github.com/opshope/32f65875d45215c3677d).

As in Windows, in MacOS you can also **hijack dylibs** to make **applications****execute****arbitrary****code**.

However, the way **MacOS** applications **load** libraries is **more restricted** than in Windows. This implies that **malware** developers can still use this technique for **stealth**, but the probably to be able to **abuse this to escalate privileges is much lower**.

First of all, is **more common** to find that **MacOS binaries indicates the full path** to the libraries to load. And second, **MacOS never search** in the folders of the **$PATH** for libraries.

However, there are 2 types of dylib hijacking:

* **Missing weak linked libraries**: This means that the application will try to load a library that doesn't exist configured with **LC\_LOAD\_WEAK\_DYLIB**. Then, **if an attacker places a dylib where it's expected it will be loaded**.

* The fact that the link is "weak" means that the application will continue running even if the library isn't found.

* **Configured with @rpath**: The path to the library configured contains "**@rpath**" and it's configured with **multiple****LC\_RPATH** containing **paths**. Therefore, **when loading** the dylib, the loader is going to **search** \(in order\) **through all the paths** specified in the **LC\_RPATH****configurations**. If anyone is missing and **an attacker can place a dylib there** and it will be loaded.

The way to **escalate privileges** abusing this functionality would be in the rare case that an **application** being executed **by****root** is **looking** for some **library in some folder where the attacker has write permissions.**

A nice report with technical details about this technique can be found** [**here**](https://www.virusbulletin.com/virusbulletin/2015/03/dylib-hijacking-os-x)**.**

### **DYLD\_INSERT\_LIBRARIES**

> This is a colon separated **list of dynamic libraries** to l**oad before the ones specified in the program**. This lets you test new modules of existing dynamic shared libraries that are used in flat-namespace images by loading a temporary dynamic shared library with just the new modules. Note that this has no effect on images built a two-level namespace images using a dynamic shared library unless DYLD\_FORCE\_FLAT\_NAMESPACE is also used.

This is like the [**LD\_PRELOAD on Linux**](../../linux-unix/privilege-escalation/#ld_preload).

This technique may be also **used as an ASEP technique** as every application installed has a plist called "Info.plist" that allows for the **assigning of environmental variables** using a key called `LSEnvironmental`.

Since 2012 when [OSX.FlashBack.B](https://www.f-secure.com/v-descs/trojan-downloader_osx_flashback_b.shtml) \[22\] abused this technique, **Apple has drastically reduced the “power”** of the DYLD\_INSERT\_LIBRARIES.

For example the dynamic loader \(dyld\) ignores the DYLD\_INSERT\_LIBRARIES environment variable in a wide range of cases, such as setuid and platform binaries. And, starting with macOS Catalina, only 3rd-party applications that are not compiled with the hardened runtime \(which “protects the runtime integrity of software” \[22\]\), or have an exception such as the com.apple.security.cs.allow-dyld-environment-variables entitlement\) are susceptible to dylib insertions.

For more details on the security features afforded by the hardened runtime, see Apple’s documentation: “[Hardened Runtime](https://developer.apple.com/documentation/security/hardened_runtime)”

It's a scripting language used for task automation **interacting with remote processes**. It makes pretty easy to **ask other processes to perform some actions**. **Malware** may abuse these features to abuse functions exported by other processes.

For example, a malware could **inject arbitrary JS code in browser opened pages**. Or **auto click** some allow permissions requested to the user;

```bash

tell window 1 of process “SecurityAgent”

click button “Always Allow” of group 1

end tell

```

Here you have some examples: [https://github.com/abbeycode/AppleScripts](https://github.com/abbeycode/AppleScripts)

Find more info about malware using applescripts [**here**](https://www.sentinelone.com/blog/how-offensive-actors-use-applescript-for-attacking-macos/).

Apple scripts may be easily "**compiled**". These versions can be easily "**decompiled**" with `osadecompile`

However, this scripts can also be **exported as "Read only"** \(via the "Export..." option\):

```bash

file mal.scpt

mal.scpt: AppleScript compiled

```

and tin this case the content cannot be decompiled even with `osadecompile`

However, there are still some tools that can be used to understand this kind of executables, [**read this research for more info**](https://labs.sentinelone.com/fade-dead-adventures-in-reversing-malicious-run-only-applescripts/)\). The tool [**applescript-disassembler**](https://github.com/Jinmo/applescript-disassembler) with [**aevt\_decompile**](https://github.com/SentineLabs/aevt_decompile) will be very useful to understand how the script works.

Red Teaming in **environments where MacOS** is used instead of Windows can be very **different**. In this guide you will find some interesting tricks for this kind of assessments:

* \*\*\*\*[**OS X Incident Response: Scripting and Analysis**](https://www.amazon.com/OS-Incident-Response-Scripting-Analysis-ebook/dp/B01FHOHHVS)\*\*\*\*