4.5 KiB

Hello World

Let's put together a simple "hello world" to get acquainted with Dioxus. The Dioxus-CLI has an equivalent to "create-react-app" built-in, but setting up Dioxus apps is simple enough to not need additional tooling.

First, let's start a new project. Rust has the concept of executables and libraries. Executables have a main.rs and libraries have lib.rs. A project may have both. Our hello world will be an executable - we expect our app to launch when we run it! Cargo provides this for us:

$ cargo new --bin hello-dioxus

Now, we can cd into our project and poke around:

$ cd hello-dioxus

$ tree

.

├── Cargo.toml

├── .git

├── .gitignore

└── src

└── main.rs

We are greeted with a pre-initialized git repository, our code folder (src) and our project file (Cargo.toml).

Our src folder holds our code. Our main.rs file holds our fn main which will be executed when our app is ran.

$ more src/main.rs

fn main() {

println!("Hello, world!");

}

Right now, whenever our app is launched, "Hello world" will be echoed to the terminal.

$ cargo run

Compiling hello-dioxus v0.1.0

Finished dev [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.41s

Running `target/debug/hello-dioxus`

Hello, world!

Our Cargo.toml file holds our dependencies and project flags.

$ cat Cargo.toml

[package]

name = "hello-dioxus"

version = "0.1.0"

edition = "2018"

# See more keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

[dependencies]

To use the Dioxus library, we'll want to add the most recent version of Dioxus to our crate. If you have cargo edit installed, simply call:

$ cargo add dioxus --features web

It's very important to add dioxus with the web feature for this example. The dioxus crate is a batteries-include crate that combines a bunch of utility crates together, ensuring compatibility of the most important parts of the ecosystem. Under the hood, the dioxus crate configures various renderers, hooks, debug tooling, and more. The web feature ensures the we only depend on the smallest set of required crates to compile.

If you plan to develop extensions for the Dioxus ecosystem, please use dioxus-core crate. The dioxus crate re-exports dioxus-core alongside other utilties. As a result, dioxus-core is much more stable than the batteries-included dioxus crate.

Now, let's edit our main.rs file:

use diouxs::prelude::*;

fn main() {

dioxus::web::start(App)

}

fn App(cx: Context<()>) -> VNode {

cx.render(rsx! {

div { "Hello, world!" }

})

}

Let's dissect our example a bit.

This bit of code imports everything from the the prelude module. This brings into scope the right traits, types, and macros needed for working with Dioxus.

use diouxs::prelude::*;

This bit of code starts the WASM renderer as a future (JS Promise) and then awaits it. This is very similar to the ReactDOM.render() method you use for a React app. We pass in the App function as a our app.

fn main() {

dioxus::web::start(App)

}

Finally, our app. Every component in Dioxus is a function that takes in a Context object and returns a VNode.

fn App(cx: Context<()>) -> VNode {

cx.render(rsx! {

div { "Hello, world!" }

})

};

In React, you'll save data between renders with hooks. However, hooks rely on global variables which make them difficult to integrate in multi-tenant systems like server-rendering. In Dioxus, you are given an explicit Context object to control how the component renders and stores data.

Next, we're greeted with the rsx! macro. This lets us add a custom DSL for declaratively building the structure of our app. The semantics of this macro are similar to that of JSX and HTML, though with a familiar Rust-y interface. The html! macro is also available for writing components with a JSX/HTML syntax.

The rsx! macro is lazy: it does not immediately produce elements or allocates, but rather builds a closure which can be rendered with cx.render.

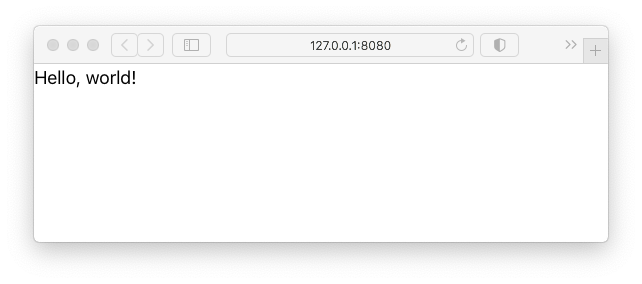

Now, let's launch our app in a development server:

$ dioxus develop

Huzzah! We have a simple app.

If we wanted to golf a bit, we can shrink our hello-world even smaller:

fn main() {

dioxus::web::start(|cx| cx.render(diouxs::rsx!( div { "Hello, World!" } ))

}

Anyways, let's move on to something a bit more complex.